UNPREPARED FOR PEACE?

The Decline of Canadian Peacekeeping Training

(and What to Do About It)

A. Walter Dorn and Joshua Libben

Published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) and the Rideau Institute, Ottawa, February 2016.

Full report available as pdf. An updated version of this paper was published in the International Journal (link).

(Cliquez ici pour une traduction française du résumé et des recommandations)

Executive Summary

Over the past decade, Canada and the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) have experienced a major decline in training and education for peacekeeping operations (PKOs), also known as peace support operations (PSOs) or simply peace operations. This development occurred in parallel with a major decline in Canadian military contributions to such operations. While Canada deployed large numbers of forces and provided key leadership for a half-century, it has deployed very low levels of personnel in UN peacekeeping over the past ten years. When the United Nations increased its forces to an all-time high in 2015 (over 90,000 military personnel), the Canadian contribution remained at an all-time low (less than 30 military personnel). This lack of participation and experience means that renewed training will be necessary if the CAF personnel are called upon to serve or lead in UN operations in the future. The complexities of modern peace operations require in-depth training and education, on subjects including the procedures, capabilities and limitations of the United Nations. Canada is currently far behind other nations in its readiness to support the United Nations and train for modern peacekeeping.

This study focuses on the training and education of Canadian military personnel, particularly the officer corps; these officers could be expected to hold important positions in future peacekeeping deployments when the country reengages. These men and women in uniform can serve in both command and staff positions, including conceivably as a Force Commander— a position held by Canadian soldiers four times in the 1990s, but not since.

A thorough review of contemporary training shows that the CAF provides less than a quarter of the peacekeeping training activities that it did a decade ago. Significantly, in exercises and simulations, Canadian officers no longer take on roles of UN peacekeepers as they once did. At CAF training institutions, courses and simulated exercises now focus primarily on the requirements of taking part in “alliance” or NATO-style operations, resulting in significantly fewer opportunities for officers to view missions from a UN perspective or gain understanding of UN procedures and practices.

The 2006–11 combat mission in Kandahar, Afghanistan, certainly gave CAF personnel valuable experience in combat and counter-insurgency (COIN) operations. While there are similarities between these types of missions and international peace operations, there are also fundamental differences in the training, preparation and practice of peacekeeping deployments. War-fighting and COIN are enemy-centric, usually non-consensual missions that primarily involve offensive tactics, whereas peacekeeping is based on a trinity of alternative principles: consent of main conflicting parties, impartiality and the defensive use of force. A major change in mentality and approach, as well as knowledge, would be needed to properly prepare Canadian Forces for future peace operations. Special skills, separate from those learned in Afghanistan and warfare training, would need to be (re) learned, including skills in negotiation, conflict management and resolution, as well as an understanding of UN procedures and past peacekeeping missions. Particularly important is learning effective cooperation with the non-military components of modern peacekeeping operations, including police, civil affairs personnel and humanitarians, as well as UN agencies, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and the local actors engaged in building a viable peace.

The decline in peacekeeping training and education in the CAF is readily apparent when looking at the primary training institutions that prepare Canadian officers for service. This study looks at the Royal Military College, the Canadian Army Command and Staff College, the Canadian Forces College, the Royal Military College Saint-Jean, the Peace Support Training Centre and the now defunct Pearson Peacekeeping Centre. Since the activities of the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) and Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) are quite similar in UN peacekeeping to other operations, this review concentrates on the army and joint training, from officer cadets to generals.

To its credit, the Royal Military College, which teaches both officer cadets and graduate students, has managed to maintain roughly the same level of peacekeeping courses over the past decade, though it no longer co-sponsors peacekeeping summer institutes. The Canadian Army Command and Staff College, which provides the Army Operations Course (AOC) to soldiers of the Captain rank, currently provides much less preparation for involvement in UN peace operations than it did. The AOC no longer offers lectures on PSOs and the United Nations, as it did a decade ago. While there is a PSO aspect in one of the major exercises, the officers do not role-play peacekeepers but are instead part of a NATO-like operation.

The Canadian Forces College in Toronto provides joint training/education for officers from the army, air force and navy. Its programmes are for the future leaders in the officer corps in Canada and selected other nations. Its activities (lectures and exercises) relating to PKOs have been reduced to less than half of what they were in 2005. The Joint Command and Staff Programme went from seven lectures and two discussions on peacekeeping in 2005 to two lectures in 2014/15, one of which is only given to one stream (roughly one third of the students). At the higher (national security) level, the case studies and exercises on peacekeeping were dropped. However, the higher-ranked students (mostly Colonels and navy Captains) continue to make a useful trip to New York City for lectures from UN and diplomatic leaders. The CFC once had an exercise where students actually role-played peacekeepers planning an operation: Unified Enforcer ran from 2002 to 2008 under the Advanced Military Studies Programme. Some current exercises play an alliance that provides offensive military capability to back a PSO but, as with the AOC, the role-playing is for NATO-like structures and not the United Nations.

The Peace Support Training Centre in Kingston was established in 1996 to focus on peace support operations but over the last decade it has lost that focus. Under the demands of the Afghanistan operation, it refocused on training and preparation for NATO-style interventions. With the exception of the “peace support operator course” (formerly UN military observer and liaison course), it does not offer any UN-specific content among its eight courses.

Finally, and most significantly, the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, which used to provide cutting-edge peacekeeping education to over 150 Canadian military personnel a year, and to many more foreign national officers, was shut down in December 2013 following the loss of federal funding. With that closure, Canada lost its main peacekeeping facility to train military personnel, police and civilians together.

When these programmes are taken in overview, the number of activities devoted to the United Nations and to peace support is far less than what it was a decade or more ago. The level of peace support training has declined to levels seen prior to the 1992–93 Somalia operation, which resulted in an extensive Inquiry which in 1997 recommended a substantial upgrade to the peacekeeping training regimen.

Training and preparedness are core elements of the mandate of the Canadian Armed Forces. The men and women of the military seek to be constantly ready for any number of operational demands that the Canadian government and people may require of them. Especially with the Liberal government’s policy of re-engagement in UN peacekeeping,1 the CAF needs to increase the level of preparedness and training for peace operations if it is to be ready to serve in peace operations. Canadian soldiers have served as superb peacekeepers in the past and can do so again, with some preparation.

To this end, this report recommends the reinstatement and updating of the many training programmes and exercises that have been cut, as well as the introduction of new training activities to reflect the increasing complexity of modern peace operations. Only through such a significant increase in training can Canadian personnel be truly prepared for peace.

1. INTRODUCTION: MODERN PEACEKEEPING

Since Canada’s disengagement with UN peace operations more than a decade ago, the complexity, scope and requirements of peacekeeping missions have increased drastically. United Nations peacekeeping forces operating in the contemporary context must contend with raging conflicts, ethnic cleansing, human rights violations, factional infighting and spoilers of the peace process, as well as threats to themselves and their mission. Peacekeepers must not only protect local populations but also get the conflicting parties to the negotiating table, a task that requires different skills and finesse from those required for combat. Modern peace missions must also engage in important tasks that are outside strictly military operations: economic and social reconstruction (i.e., peacebuilding); election of transitional governments and the implementation of transitional justice; assistance to secure law and order; and a host of other tasks in addition to the traditional task of negotiating and monitoring ceasefires and peace agreements. To be effective in modern operations, peacekeepers need to know about a myriad of procedures within UN’s Departments of Peacekeeping Operations (DPKO) and Field Service (DFS) and the complicated UN family of agencies and non-governmental organizations working as partners in the field.

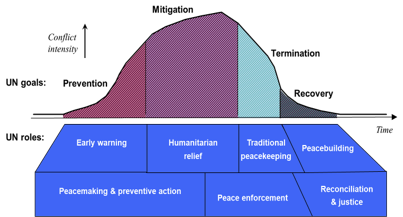

The major functions of modern peace operations are illustrated in Figure 1, using terminology from UN, NATO and Canadian doctrine. At different stages of a conflict, the goals and roles change, though virtually all the listed tasks and activities are needed in all stages, to a greater or lesser degree. As the conflict first becomes inflamed, the main UN goal is the prevention of escalation, which requires early warning tools and pre-emptive action. “Peacemaking,” in UN and NATO doctrine, is the main tool here: the negotiation of a ceasefire or peace agreement. However, if this fails and the conflict becomes full-fledged, the UN must engage mostly in mitigation, using humanitarian relief to save lives and, in the most severe cases, peace enforcement against recalcitrant parties who are committing atrocities. As the conflict winds down and the termination phase is achieved through conflict weariness and/or diplomatic intervention, a ceasefire can be agreed upon. At this point traditional peacekeeping can play a major role in maintaining the ceasefire and a potential peace agreement, sometimes by creating buffer zones or physical space between conflicting groups. In the recovery stages, the United Nations must engage in peacebuilding to develop the infrastructure, social as well as physical, that will ensure a sustainable peace and a growing economy. This period also necessitates reconciliation between the former belligerents, which can take the form of Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, tribunals, or referrals to the International Criminal Court.

FIGURE 1: Simplified Schematic Showing Conflict Intensity Over Time and the UN’s Corresponding Goals and Roles

As Figure 1 indicates, the operational demands placed upon the modern peacekeeper are far greater than the requirements typical during Cold War–era peacekeeping missions. “Traditional peacekeeping” primarily involved a small force interposed between two belligerents, or unarmed monitors covering a ceasefire or demilitarized zone, the Canadian Peace Support Operations Joint Doctrine Manual correctly noted in 2002.

Few peace support operations now follow the traditional template. Both the military and civil requirements in modern multi-disciplinary peace support operations far exceed those of traditional missions. The wider range of mil- itary tasks can include assisting in disarmament and demobilization, monitoring of elections, de-mining assistance, restoration of infrastructure and conducting concurrent enforcement operations.4

In the 1990s and early 2000s, especially following the Somalia debacle and inquiry, the Department of National Defence recognized the need for specialized training to prepare for such difficult and unique environments. Substantial progress was made from 1995 to 2005. But, as we shall see, the decade that followed saw a shift in doctrinal thinking and a substantial reduction in training for peacekeeping.5

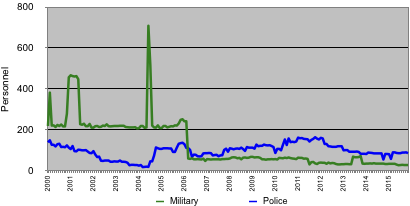

Not only is UN peacekeeping more complex; it has become much larger. The United Nations deploys over 100,000 uniformed personnel (military and police) in field operations, more than any other body, including the US government after the drawdown in Afghanistan and Iraq. The graph of deployed UN peacekeepers is shown in Figure 2. The civilians deployed in UN PKO number about 20,000, so at present the UN deploys about 125,000 UN personnel in peacekeeping. About 120 countries contribute to peacekeeping, so any Canadian peacekeepers have to work with a large range of partners of varying skill sets.

FIGURE 2. Number of Uniformed (Military and Police) Personnel in UN Peacekeeping Operations since 2000

Source: data from the UN DPKO, graph by W. Dorn (black: total; green: military; blue: police)

The number of field operations being conducted has dramatically increased as well. With the recent deployment in the Central African Republic, there are currently 16 UN peacekeeping operations being conducted across four continents. The mandates of modern peace operations are growing increasingly robust. The Force Intervention Brigade deployed to the Eastern Congo in 2013 received the first UN Security Council mandate for “offensive operations” against rebel groups. There are strong indications that, in the post-Afghanistan period, the burden of addressing emerging international crises is increasingly shifted towards the United Nations, with NATO limiting its intervention primarily to air strikes such as those used in Libya in 2011.

While the number of personnel deployed in the field by the United Nations is now at an all-time high (see Figure 2), the Canadian Armed Forces’ contribution (shown in Figure 3) has stayed at an all-time low: 28 military personnel in UN missions (as of 30 November 2015). In its military contributions, Canada is ranked well below countries such as Tunisia and Mongolia and any of the permanent members of the Security Council. Canada’s primary contribution of personnel to international peacekeeping is now mainly in the form of the police officers (85 in number, almost three times the number of military personnel). These police officers are currently concentrated in the UN’s Haiti mission. Even including these police contributions, however, Canada ranks 66th of 121 UN member states contributing uniformed personnel.

FIGURE 3. Canadian Military and Police Contributions to UN Peacekeeping since 20007

Source: data from the UN DPKO, graph by W. Dorn

As shown in Figure 3, the CAF contributions declined considerably in March 2006, as the newly elected Conservative government closed out Canada’s task force in the Golan Heights, Syria. This task force had played a major logistics role in the UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) since the mission’s creation in1974. Canada also provided the Force Commander for UNDOF in 1998-2000, the last time the country was given military command of a UN mission. By contrast, Canadian police forces (mostly RCMP) have provided the Police Commissioner in the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) for almost the entire time since the mission’s creation in 2004.

The loss of CAF experience in the field since 2005 carries a high price. The Canadian Armed Forces, which once deployed in large numbers, now has little peacekeeping experience on which to base its contributions to UN PKOs. The methods, standards, numbers and doctrines of the United Nations have all evolved considerably over the past decade as the UN experienced the surge of the new century (Figure 2), but Canada has not kept up. Neither has CAF doctrine: the PSO manual has not been updated since 2002.8

The growing complexity and scope of peace operations has significantly increased the training requirements for military personnel deployed in radically different mission environments across the world. In its assessment of global peacekeeping training needs, the United Nations reported:

Given the dynamic nature of peacekeeping and the unique challenges that peacekeeping personnel face on an everyday basis, there is a need to ensure that they are adequately equipped with the knowledge, skills, and attitudes required to perform their duties. Peacekeeping training is a strategic investment that enables UN military, police, and civilian staff to effectively implement increasingly multifaceted mandates.9

If Canada is to deploy military personnel to UN operations or provide leaders (commanders) in coming years, and lead an international peacekeeping training initiative (all promises of the new Liberal government10), the training requirements for Canadian personnel will be even greater than they were in the 1990s. Unfortunately, as we shall see in the next section, training mechanisms and institutions involved in peacekeeping have been steadily eroding since the turn of the century, especially over the last decade, to the extent that Canada is in danger of becoming fundamentally unable to field adequately trained peacekeepers. General-purpose combat training is important but not sufficient (see “Myth 2” below).

The Trudeau government seeks to “renew Canada’s commitment to United Nations peace operations.”11 In his mandate letter to the Defence Minister, Prime Minister Trudeau included the tasking of “providing well-trained personnel to international initiatives that can be quickly deployed, such as mission commanders, staff officers, and headquarters units; and leading an international effort to improve and expand the training of military and civilian personnel deployed on peace operations.” In order to understand how this can be achieved, we must look back at how training has changed in the main CAF institutions and stages over the last decade.

2. PEACEKEEPING TRAINING: THEN AND NOW

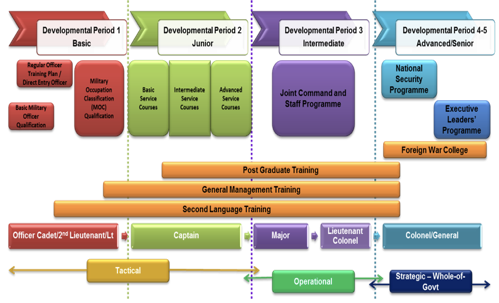

The Canadian Armed Forces, like most militaries, expends a great deal of effort on training and education. It is a continuous process and different institutions are designated to provide courses, exercises, seminars, etc., to different rank-levels. For officers (commissioned members), the system, shown in Figure 4, is broken down into five developmental periods (DP), progressing from officer cadet to general and flag officer.

For the purposes of assessing the changes in peacekeeping training and education provided to CAF officers over the last ten to fifteen years, this section will examine the courses, exercises and other activities provided by the five primary military learning institutions that, historically, have provided training/education to Canadian officers: Royal Military College (Kingston), Canadian Army Command and Staff College (Kingston), Canadian Forces College (Toronto), Peace Support Training Centre (Kingston), Roay Military College (Saint-Jean) and Pearson Peacekeeping Centre (now defunct, formerly in Cornwallis, NS, and Ottawa).12

FIGURE 4. CAF Professional Military Educational (PME) Spectrum

Source: Canadian Forces College, “CFC Overview Briefing to CFC Staff,” 14 Aug 2014

Table 2. Developmental Periods for Officers in the Canadian Forces

Source: Department of National Defence, Officer Development Periods, http://www.forces.gc.ca/en/training-prof-dev/officer.page and

Department of National Defence, DAOD 5031– Canadian Forces Professional Development, 2003.

Rank abbreviations are as follows: officer cadet/naval cadet (OCdt/NCdt); second lieutenant/acting sub-lieutenant (2Lt/A/SLt); Captain (Capt); lieutenant (Navy) /Lt(N); second lieutenant/acting sub-lieutenant (2Lt/A/SLt); lieutenant/sub-lieutenant (Lt/SLt); captain/lieutenant (Navy; Capt/Lt(N)); major/lieutenant-commander (Maj/LCdr); lieutenant-colonel/commander (LCol/Cdr); colonel/captain (Navy) (Col/Capt(N)); general/flag-officer (Gen/FO)

1. Royal Military College (RMC) of Canada

Officer Cadets (DP1) & Post-Graduate Studies

The Royal Military College of Canada is the only degree-granting federal university. Located in Kingston, Ontario, it prepares candidates for service in the Canadian officer corps. Though primarily oriented towards educating Officer Cadets in the 1st Developmental Period (DP1), the RMC also provides undergraduate and graduate programmes of study for other members of the Forces and for civilian students.

RMC is one of the few Canadian military institutions that has not seen its peacekeeping content decline since the early 2000s. All of the courses from 2001/2002 relating to UN peacekeeping continued in the 2014/2015 academic year (see Annex 1). There has been some re-naming of courses: an undergraduate political science course POE410 changed its name from “Advanced Studies in the Evolution and Theory of International Peacekeeping” to “International Conflict Management.” The two-credit War Studies course “International Peacekeeping” (WS508) was broken into two one-credit courses: “Evolution and Theory of International Peacekeeping” (WS509) and “Contemporary Peace and Stabilization Operations” (WS511). But, based on the course descriptions, there has been little change in the peacekeeping coverage of these courses.

The peacekeeping summer training institute that RMC co-sponsored has been cancelled. RMC had entered a partnership with the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre (PPC) and Acadia University to sponsor a rigorous graduate-level credit and certificate programme in peacekeeping/peace operations in 2001-2004, through the jointly administered International Peacekeeping Summer Institute (IPSI) and then the Peacekeeping Operations Summer Institute (POSI). The institutes were held at the locations of the main partners: 2001 (Acadia), 2002 (PPC), and 2004 (RMC) for credit.

Across the water (Cataraqui river mouth) from RMC in Kingston is the Canadian Army Command and Staff College, located at Fort Frontenac, informally called “Foxhole U.” It is for officers who have substantial experience after graduating from RMC.

2. Canadian Army Command and Staff College (CACSC)

Captains and Equivalents (DP2)

Soldiers of various ranks (second lieutenants, lieutenants, captains and majors) undergo training and education at the CACSC through the Army Junior Staff Qualification, the Army Operations Course (AOC), and the Command Team Course. The AOC is the main course, now consisting of seven weeks of distance learning (DL) followed later by 3-4 months in residence.13 In the DL part, PSO-specific material is currently found in the section on “Canadian Army Doctrine of Stability Operations,” mostly in the student-led tutorial exercise on “Stability Operations and Influence Activities.” The exercise has two parts and is conducted in sub-syndicate, “with one group working in a COIN context and the other working in a Peace Support Ops context.” Thus only half the students in the course get two hours of PSO material during the DL portion of course. The other PSO-specific learning comes in the exercises held in Kingston.

In Exercise METRO ASSAULT officers plan an urban offensive and then seek to create conditions needed for a handover to a stability operation. In Brigade Ex METRO GUERRIER, they also plan and execute an offensive urban operation, followed by planning for stability operations. The plan envisions that Canadian elements will remain to conduct a PSO before turning over to a UN force. So officers gain an awareness of stability functions and a general idea of the UN role, but they do not play the role of UN peacekeepers.

In Exercise MAPLE SHORE,14 soldiers simulate a counter-insurgency operation (COIN) in a fictitious country called “Isle” (based on a map of Haiti). The overall mission is led by the United Kingdom under UN Security Council authorization. The task force, under US command, is mandated to “create and maintain a safe and secure environment in WI [West Isle] within which HA [Humanitarian Assistance] can be distributed, and which will allow the development of government institutions and the promotion of economic well-being and human rights.” The tasks include “defeat” of factions, disarmament of all factions opposed to WI government, the provision of humanitarian aid and counter-IED measures. It is very Afghanistan-like in mandate and method, though not in geography.

Exercise FINAL DRIVE is designed to cover the “full spectrum” of operations. Students initially plan for a ceasefire and a stability operation (including establishing a zone of exclusion and separation and demilitarization, and supporting the return of refugees and detainees and PWs [prisoners of war]. They also plan infrastructure projects. They plan and conduct combat operations and concurrently plan for the transition back to a stability op. In planning both combat and stability operations, the student must consider key stakeholders, including the host nation, the United Nations, NGOs, and the various ethnic groups that comprise the human terrain. Again the emphasis is on the transition between combat and stability operations, not on conducting a UN operation.

In 2005, there was a lecture devoted to the United Nations and Peace Support Operations. Currently there is no lecture dealing with the topic, though mention is made of PSOs during other lectures. In the exercise emphasizing combat and COIN over PSOs, there is considerably less material currently devoted specifically to the UN operations.

The Civil-Military Seminar, held over two days, does not cover the UN or PSOs but has included briefs on a number of relevant themes, such as NGOs in disaster management, Plan Canada, Global Medic, Adventist Development and Relief Agency (ADRA), World Vision, 1st Canadian Division, civil-military cooperation (CIMIC), Haiti hurricane path / vegetation map, the Disaster Assistance Response Team (DART), and the UK Comprehensive Approach.

Selected army officers, after being promoted to Major or Lieutenant Colonel, may get the chance to further their education by joining officers from the Navy and Air Force at the Canadian Forces College in Toronto.

3. Canadian Forces College

Majors and Lieutenant Colonels and Naval Equivalents (DP3)

At the DP3 level, selected Majors and Lieutenant Colonels (Navy Commanders) take the Joint Command and Staff Programme (JCSP) from the Canadian Forces College, either in residence or by distance learning. The JCSP programme was introduced in 2005 to replace the Command and Staff Course (CSC). With this shift came a significant loss in PSO material, including the only exercise of a strictly peacekeeping nature. Annex 2 shows the course changes over time.

For coursework relating to PSOs, in 2001/2002, students taking courses at the CFC had 8 lectures, 1 discussion group, and 1 seminar, amounting to around 15 hours of contact time. By comparison, the last JSCP (serial 41, 2014/15) offered only one lecture to the entire course on the United Nations and none on peacekeeping. In one of the three distinct streams, there was a lecture on “The Evolution of Peace and Stability Operations” but it was only available to about one third of the JSCP residential students. In 2015/16 the programme (JSCP 42) offers an elective (“complementary studies”) course on “Peace and Stability Operations: An Evolving Practice.” This course is only offered to a small number of students (15), given that it is only one of nine or so electives on offer.

The most relevant exercise at CFC, Exercise Friendly Lance, was conducted from 2001 to 2005. It simulated a UN Peace Implementation Force and often involved expert consultants from the United Nations and the Canadian government providing advice on the conduct of peace operations. In JCSP, this exercise was replaced with Warrior Lance, a simulated exercise involving a far more enforcement-type operation (a NATO-style international intervention). As of 2014/2015, even Exercise Warrior Lance, which at best had a tangential connection to Peace Support Operation training in the previous year, has been retired. In the JCSP 41 (2014/15) program, there was no United Nations or peacekeeping element in any of the simulated exercises carried out by DP3 officers at the CFC. (See Annex 2.)

Colonels and Naval Equivalents (DP4)

The National Security Programme (NSP) is designed for Colonels and occasionally recently promoted Brigadiers, as well as executive-level civilians in the Canadian public service. The officers are the future military leaders of Canada and other nations. Despite the strategic level and international flavour of the programme, under the current training regime these officers receive only a single lecture-discussion at CFC on the United Nations.15 However, they visit New York for 2-3 days in an Experiential Learning Visit (ELV). This gives them good exposure to the United Nations officials and national diplomats, though they do not have meetings inside UN buildings but only at Canada’s Permanent Mission. A listing of UN and PSO related activities for current and past NSP serials is provided in Annex 3.

A decade ago, DP-4 officers took part in two distinct, now replaced, course programmes: the Advanced Military Security Course (AMSC) of three-month duration and the National Security Studies Course (NSSC) of six-month duration. (The current NSP is of nine months’ duration, a kind of combination of the two earlier courses.) In NSSC 7 (2005) there were many more activities on the UN and PSOs: a lecture discussion (“Canada and the United Nations,” held in NYC), a lecture (“International Organizations”) and a Case Study (“Op Assurance – Zaire”). The AMSC had a “PSO Symposium” of 1.5 days but this was last held in 2005. It included lectures, seminars and discussions on issues like “Conflict Termination and Resolution” and “Canada and the UN,” amounting to 10.5 hours of course time.

With regard to exercises, Unified Enforcer was the only DP4 exercise that simulated peacekeeping, though not a UN force but a Multinational Peace Support Force under a NATO-like alliance. Still, it was a PSO mission, deployed with the consent of conflicting parties under a peace agreement. The exercise ran from 2002 to 2007 under AMSP. In subsequent years, NSP ran Exercise Strategic Power, wherein students are asked to plan a Canadian contribution to a coalition mission similar to the 1999 NATO intervention in Kosovo. There, students can interact with consultants who provide advice about UN agencies/operations, but the students do not plan peacekeeping operations or role-play peacekeepers or UN commanders.

In summary, from 2005 to 2015 the amount of CFC material covering PSOs and the UN has decreased to less than a quarter.

General and Flag Officers (DP5)

To round off the professional development survey for officers, the highest level is DP5 for general and flag officers. There are almost no courses at this level since the traditional thinking has been that officers who reach this level already have considerable training and education, and can also teach themselves, mainly on the job. (This approach is currently being reconsidered.) The Executive Leaders Programme (ELP), held for one week annually at the Canadian Forces College, is one such course programme, and currently has no session on UN peace operations. The course is taught at a high strategic level.

On the other end of the career and rank spectrum is the training of new recruits and non-commissioned members. Much of this is done in Saint-Jean.

4. Royal Military College Saint-Jean

Located at Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu in Quebec, RMC Saint-Jean focuses on providing CEGEP college-level education to officer cadets selected from high schools, in Quebec and from other provinces, prior to further university-level education at RMCC in Kingston. The cadet programmes at RMC Saint-Jean last one or two years, with both the science and social science programmes, and a focus on the four pillars of both military colleges (academics, leadership, athletics, and bilingualism). The goal of these programmes is to provide DP1 cadets with a broad education, typical of the senior year of high school in other provinces and the first year of university. There are no peacekeeping-specific courses at this level, in part because the College must follow the curriculum designed by the Quebec Ministry of Education.16

In addition to its cadet programme, Saint-Jean is home to the Chief Warrant Officer Osside Profession of Arms Institute which trains and educates future leaders of the Canadian Forces NCM corps. In this capacity, instructors and Faculty at Saint-Jean conduct an Intermediate Leadership Programme (ILP), Advanced Leadership Programme (ALP) for CPO2/MWO, the Senior Leadership Programme (SLP) for CPO1/CWO, and the Senior Appointment Programme qualification for specially selected Chief Petty Officers/Chief Warrant Officers.

Currently, the largest number of NCMs receive their training through the ILP; this involves 10 weeks of distance learning and 3 weeks of residential learning, on issues that form the basis for almost all forms of military operations. As shown in Annex 5, in 2004-05, there were many teaching points relating to peacekeeping, including “The Suez Canal Crisis and the beginnings of peacekeeping (1956),” “The application of the Medak Accord in Croatia (1993),” “Rwanda: Operation Assurance (1996)” and points on “Canada’s military obligations within NATO and the UN.” Perhaps most relevant was a teaching point on “Identifying the types of peace support operations.” No similar points were found in the 2014/15 curriculum. In the more recent Intermediate Leadership Programme, the 25 Performance Objectives (POs) cover topics from Canadian Military History to Communication Strategies, but none are explicitly on PSOs or the United Nations. The closest is a PO on “Interact during operations with International Organizations (IOs), Non-Government Organizations (NGOs), Other Government Departments (OGDs) and the Host Nation.” We understand that specific teaching points of this PO are still being written.

Similarly, no direct peacekeeping course-content was found for the senior course (SLP) for 2014/15. There were only two Enabling Objectives where peacekeeping might be mentioned: EO 5E2.01 (“Apply JIMP Doctrine within a Canadian Comprehensive Approach to Plans and Operations”) and 5E2.02 (“Sustain the Whole of Government Approach”). In conclusion, compared to 2004, there is a significant lack of PSO-specific teaching to future NCM leaders being done at Saint-Jean.

5. Peace Support Training Centre (PSTC)

Unlike the institutions described above, the Peace Support Training Centre was created with peacekeeping specifically in mind. The PSTC, located within Canadian Forces Base Kingston, was stood up in 1996, in response to the Canadian Forces’ own recognition of a major lack of peacekeeping training. The debacle in 1993 in Somalia operation was a major motivating factor. The Somalia Inquiry’s final report (1997) found the following in the run-up to the Somalia operation:

There was no formalized or standardized training system for peace operations, despite almost 40 years of intensive Canadian participation in international peace operations. No comprehensive training policy, based on changing requirements, had been developed, and there was an absence of doctrine, standards, and performance evaluation mechanisms respecting the training of units deploying on peace operations ….

Indeed, at that time (1992), the training policy of the CF [Canadian Forces] was based almost exclusively on a traditional mode of general purpose combat preparation ….17

The Somalia Inquiry urged that all Canadian Forces members receive PSO training from the PSTC. The Basic PSO course became the staple of the Centre for many years.18 However, after the Kandahar deployment in 2005-06, the PSTC changed its course offerings. The Basic course dropped from 88 percent of the training calendar to 45 percent.19 Rather than focusing on PSO, the PSTC diversified to meet the operational need, taking on a much wider array of tasks than its name suggested.

In 2008, the PSTC transformed the Basic Peace Operations Course into the Individual Pre-Deployment Training course. With this shift, the course and the Centre itself became significantly more combat-oriented. Whereas before the PSTC’s focus was on UN deployments, with an emphasis on peace support operations and duties, the pre-deployment regimen emphasized weapons drills, the use of force, and information security. Many of the combat skills that were previously taught by a soldier’s home unit, such as firing a service rifle, defending against chemical, biological, nuclear and radiological materials (CBNR), and throwing grenades, became a core part of what had been the Basic Peace Operations Course. Among the items dropped was “Peace Support Operations – General Mission and Mission Area Information,” and “Peace Support Duties.”

By 2014/15 only one of its eight courses was on peacekeeping: the Peace Support Operator Course. Like the CAF as a whole, the PSTC shifted its training to “Full-Spectrum Operations (FSO) within the contemporary operating environment.”20 And, during Canada’s combat involvement in Afghanistan (2006-11), the PSTC was re-geared to counter-insurgency missions. Still the Peace Support Operator Course remained. Formerly known as the Military Observer (MILOBS) course, it includes foreign military participants as well as Canadians from the military and civilians on the International Standby List. Simulating an operational theatre with specifics of language, culture, and belligerent parties, students are instructed in traditional peacekeeping skills such as observing and reporting, manning observation posts, patrolling, and negotiating/mediating. Additionally, they are given skills in mine awareness, first aid and ethics. Over the 30-day course, students are expected to learn about “the law of armed conflict (LOAC), Canadian defence ethics and army ethos, potential ethical dilemmas facing soldiers deployed in PSO, and conduct expected of individuals representing the UN in operations.”21

The Centre offers courses for both commissioned and non-commissioned personnel. Offered to all DP levels, the Individual Pre-Deployment Training (IPT) course consists of 18 days of training to “teach the individual skills necessary to appropriately respond to the intercultural and potentially hostile nature of a Land-Based Operations environment.”22

The other courses the PSTC offers are on Information Operations, Individual Battle Task Standards (IBTS), Psychological Operations, and Civil Military Transition Team. There is also a somewhat PSO-related course in Civil-Military Cooperation (CIMIC). The CIMIC Operator Course for ranks of Lieutenant or higher (officers), Sgt. or higher (NCMs), can be quite useful for PSOs, though it is designed for a broader set of operations. The 13-day course is run four times a year for members who have been selected for CIMIC employment. The Centre also runs once a year a CIMIC Staff Officer Course for Captains or higher (warrant officer or higher for NCMs). Although interaction with other government agencies and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) is an inevitable part of every peacekeeping operation, the CIMIC courses do not directly include peacekeeping-specific training. A full list of courses is provided in Annex 6.

The PSTC is still officially the CAF’s Centre of Excellence for PSOs and maintains a facility including two simulated United Nations observation posts, a simulated village and a mine-awareness training area. The CAF members who have gone through pre-deployment training at the PSTC flagged the lack of cultural awareness training in the program, noting that such training was limited to “a couple of days of language.”23 Even for combat-heavy deployments in Afghanistan, many members felt that the PSTC might have provided more cultural and theatre-specific education to better prepare them for their missions. This trend towards combat-only training at the Centre is not in line with the recommendations made by the Somalia Inquiry in 1997, whose report in part led to the founding of the Peace Support Training Centre. The Inquiry recommended the following:

The Canadian Forces training philosophy be recast to recognize that a core of non-traditional military training designed specifically for peace support operations (and referred to as generic peacekeeping training) must be provided along with general purpose combat training to prepare Canadian Forces personnel adequately for all operational missions and tasks.24

We have found, however, that the PSTC provides much less than a quarter of peacekeeping training to its participants as compared to a decade ago.

6. Pearson Peacekeeping Centre

The Pearson Peacekeeping Centre (still often referred to as PPC even after being renamed the Pearson Centre) was originally created by the Canadian government as a peacekeeping training facility for officers and civilians from Canada and around the world. Headquartered in the former military facility of Canadian Forces Base Cornwallis in Nova Scotia, the PPC operated the Cornwallis facility from 1994 until 2012. (The full closure of the Pearson Centre occurred in November 2014.) Under the rubric of “the new peacekeeping partnership,” the PPC was the first international peacekeeping training centre to include integrated civilian and military peacekeeping training modules. At its height in the 1990s and early 2000s, Cornwallis hosted over a dozen courses per year, focusing on preparing civilians, police, and military personnel for deployment in UN peacekeeping operations. A list of course titles and exercises is provided in Annex 7.

The PPC initially operated with core funding of about $4 million, provided equally by the Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade (DFAIT) and the Department of National Defence (DND).25 DND also paid tuition fees for students and the salaries of personnel seconded to the PPC. It also paid tuition and travel fees for foreign military personnel attending PPC through Canada’s Military Training and Assistance Programme (MTAP). In the first decade, over half of the students were CAF officers. Approximately 150 Canadian Forces military personnel attended courses at PPC per year.26In 2006-07, there were 431 Canadian participants (military and civilian) in various PPC projects for the year (around 22% of the total participant population).

The United Nations Integrated Mission Staff Office Course (UNIMSOC or C99) was held annually over six weeks at the PPC’s Cornwallis campus in Nova Scotia. After 2006, this course was supplemented by a three-week Senior Management Course (SMC) on UN Integrated Missions, aimed at teaching upper-level military officials about the planning, political and strategic aspects of peace missions. But by 2011 there were no Canadian Forces officers in the UNIMSOC and SMC courses. The vast majority of students come from Africa, with some from Latin America and South Asia.

The PPC also began supporting travelling courses, held in an impressive set of locations abroad (Brazil, Chile, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Ghana, Mali, Senegal, South Africa and USA) and in Canada (Halifax, Gagetown, St. John’s, Ottawa and Toronto). In 2006, the PPC educated four times as many international participants (1,691) as Canadian participants (393).27

Despite this enviable record, a year after the new government came into power in 2006, the Chief of Review Services concluded that DND should cease its contribution to the core funding of PPC, first for the PPC’s training programmes in Canada and then to the institution as a whole.28

With the 2013 closure of the Pearson Centre and the loss of the Cornwallis facility, a unique resource for peacekeeping training, and an important educational and practical asset, was lost, leaving Canada with no facilities or institutions dedicated to the joint preparation of military, police and civilians for peacekeeping deployment.

One of the major achievements of the PPC was to serve as a model for the establishment of other peacekeeping training centres. The PPC was a founder of the International Association of Peacekeeping Training Centres (IAPTC), which has grown to over 260 member organizations in over 30 countries.29 The first IAPTC meeting was held at the PPC. It is ironic that Canada’s pioneering institution is now defunct and no longer contributing to the IAPTC or the advancement of peacekeeping training and education at a time when cutting-edge thinking is still needed.

7. Other Training

Due to the decentralized manner in which members of the Canadian Armed Forces, commissioned and non-commissioned, are trained at the unit level, it is difficult to comprehensively assess the changes and trends in peacekeeping training for these troops over the last ten to fifteen years. Much anecdotal evidence, however, points to the lack of unit level training for peacekeeping. Additionally, because the majority of deployments of Canadian Forces in peace operations since 2002 have involved officer-level deployments on an individual basis, rather than formed units, this report has primarily focused on the dynamics of officer training, rather than NCMs.

For specific trades, some UN-specific training has been carried out in the past. For instance, a two-week “United Nations Logistics Course” was held annually at the Canadian Forces School of Administration and Logistics in Borden, Ontario, but the course was discontinued in the mid-2000s. Until that point it proved particularly useful for logistics officers who were deployed to the UN’s mission on the Golan Heights, a contribution that Canada dropped in 2006 after 32 years.

8. Foreign Officer Training

The decline in peacekeeping training provided by the Canadian Armed Forces is not limited to its own soldiers. The number of foreign nationals trained to serve in PSOs has declined as well. The loss of the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre had a major impact on training of international students. Also, the government cut the military assistance it provides to other countries in the form of training and education.

The Department of National Defence established various military training programmes for foreign officers as part of a “defence diplomacy” initiative. These were under the Military Training Assistance Programme (MTAP) later renamed the Military Training and Cooperation Programme (MTCP) under the Directorate – Military Training & Cooperation (DMTC). These programmes have provided military training and education programmes to over 70 developing, non-NATO countries. PSO training is less controversial than combat training (given that combat training can more easily be misused), so much of the focus has been on PSO training. The programme conducts activities for foreign officers both inside Canada (mostly at the PSTC) and outside (through cooperation with host nations), improving the language capabilities of students, their professionalism and their capacity to undertake multilateral PSOs.

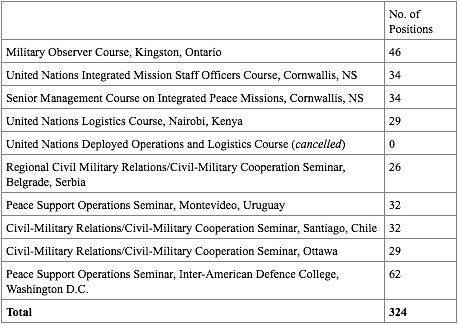

In 2008-09, the MTAP annual budget was $22 million, with a significant focus on training for officers of the Afghan National Army rather than traditional peacekeeping training. Table 3 provides a snapshot (for Fiscal Year 2008/09) showing the nine CAF-sponsored courses with foreign military personnel training through the MTAP-MTCP program. With the end of NATO-led military operations in Afghanistan and a general reduction in defence spending, the budget was reduced to $15 million in 2015/16.

Table 3. Canadian PSO Training for Foreign Military Personnel through MTAP 2008/09

Source: Summative Evaluation of the Contribution Agreement with MTAP, March 2009, 1258-117-3 (Chief of Review Services), p.11. Annex D.

Available at http://www.crs.forces.gc.ca/reports-rapports/pdf/2009/121P0883-eng.pdf.

A three-week Tactical Operations Staff Course (TOSC) ran for 22 series from 2005 to 2012 in peacekeeping training centres in countries like Kenya, Ghana and Mali. It graduated more than 500 students over seven years, and held exercises where foreign students role-played as UN peacekeepers in detailed and realistic simulations. Until 2013, there was also a Joint Command and Staff Course (JCSC) held in Aldershot, Nova Scotia, to prepare UN Member Nation officers for possible future staff positions in PKOs. Soon after the closure of the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre, however, the Aldershot school was closed due to a lack of funding.

The Directorate of Military Training cooperation continues to hold the United Nations Staff Officer Course (UNSOC) and the United Nations Integrated Mission Staff Officer Course (UNIMSOC) annually, using training institutions in Africa and South America a venues for training officers from developing countries for peacekeeping deployment.

The Canadian Defence Academy (CDA) organizes Senior Officer Seminars, about five per year for about 30 foreign officers per course. Each course is done with a foreign partner, such as Botswana, Brazil, Colombia, Indonesia and Serbia. In these seminars, PSOs and civil/military cooperation are often the theme. For instance, one seminar, funded by DMTC, was called the Senior Officer Peace Support Operations (SOPSO) Seminar, held in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in 2012.

Ironically, given the cuts to Canadian-based peacekeeping training in recent years, Canada has been training more foreign officers in UN operations than it has its own officers. But even that has decreased due to a lack of funding. In addition to the lack of political support for PSOs under the Harper government, there were enduring myths in the CAF that held back the development of PSO training.

3. THREE MYTHS ABOUT PEACEKEEPING AND TRAINING

#1. Peacekeeping missions are low-intensity, low-level operations.

This myth stems primarily from the Cold War experience that peacekeeping missions mostly act as buffer zones between relatively stationary armies. Many therefore believe that, compared to NATO operations like the one in Afghanistan, UN peacekeeping operations are simple and easy. As described earlier in this report, however, the mandate and complexity of peace operations have evolved considerably since the end of the Cold War. To deal with the switch from interstate to intrastate conflict, modern operations became multi-dimensional, requiring highly trained and dedicated personnel who are intensely familiar not only with the specifics of their deployment, but also the operational mechanics that are unique to the United Nations, and to the limits of the Security Council mandate. The peacekeepers seek to meet very high post-war expectation under demanding circumstances. They must also be well prepared for combat, especially to repel attacks by spoilers of the peace process.

As examples, the ongoing UN operations in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and in Mali are particularly complex and deadly. The mission in the Congo has a Security Council mandate for “offensive operations” against illegal armed groups, meaning that parts of the force are authorized to disarm such groups by force if necessary and neutralize them if need be. The peacekeepers in Mali, meanwhile, must take measures to prevent or mitigate deliberate attacks against themselves and the civilian population at considerable risk to themselves. Since its creation in 2013, the UN mission in Mali has suffered 44 combat fatalities, making it one of the most dangerous peacekeeping or peace enforcement missions. In order to be effectively deployed to these missions, peacekeepers must be specially trained in combat. They must also work alongside a wide array of different national forces from both the developed and the developing world, as well as with the diverse array of non-military peacekeepers for common protection and implementation of the mandate. These are not low-intensity operations requiring low skill levels. To be effective, the peacekeepers need to be well trained.

#2. General combat training is sufficient to prepare troops for peacekeeping deployment.

If the idea that peacekeeping is a low-intensity, “easy” deployment of armed forces is false, it is also untrue that soldiers trained for combat operations are sufficiently trained to be peacekeepers. The complex environments faced by UN peacekeepers demonstrate that the old notion that the best way to train a peacekeeper is to train a general-purpose, combat-capable soldier is no longer appropriate, if it ever was. While combat training remains essential for UN soldiers, much additional and specialized training is required. In Canada, the last fifteen years have seen a particular focus on training for NATO-style international interventions, given the CAF’s high-profile role in Afghanistan. However, modern peacekeeping missions involve fundamentally different dynamics facing personnel deployed on the ground, including a strong emphasis on negotiation and increased restrictions on the use of force.

While some aspects of the CAF experience in Kandahar may be transferable to future peacekeeping deployments, there is also a need for dedicated courses, exercises and training institutions to provide preparation for peacekeeping. It is not sufficient for the CAF to train purely for war-fighting on the assumption that preparation can be “scaled back” for stability operations like peacekeeping. Canadian soldiers need skills outside the domain of traditional war-fighting training (such as non-lethal weapons, de-escalation tactics and negotiation skills) to ensure the “qualitative readiness” for possible future operations.30

A report by the International Peace Institute stated: “the role of training in the success or failure of UN peacekeeping operations is generally understated.... In practice, special training is needed because UN peacekeeping involves more than the basic military tasks for which soldiers are – or should be – already trained.”31

The United Nations has also emphasized to its member states the need for specialized training of national troops in the pre-deployment stage. The UN’s Global Training Needs Assessments identified the training priorities of the following: understanding the United Nations and peacekeeping institutions and processes; mandated tasks (such as protection of civilians, child protection, promotion of human rights) and cross-cutting issues such as gender and how to integrate them in one’s work; and the application of UN peacekeeping fundamental principles (like consent, impartiality and non-use of force except in self-defence and defence of the mandate).32

#3. Canada’s low level of engagement in peacekeeping operations has lessened the need for peacekeeping training in Canada.

For decades Canada was recognized internationally as a leader in UN peacekeeping. It provided the largest number of troops during the Cold War and in the early 1990s it still held the number one spot (e.g., with some 3,300 troops in July 1993), operating in diverse locations such as Bosnia, Cambodia and Somalia. Figure 3 showed the number of Canadian uniformed personnel deployed from 1990 to the present. While the number of personnel deployed in the field by the United Nations is now at an all-time high (over 100,000 uniformed personnel), the Canadian Forces’ contribution is at an all-time low (with only 27 military personnel currently deployed). For some, this low level of engagement with United Nations peacekeeping justifies the cuts in training infrastructure that have been exhibited over the last decade. After all, what is the point of holding a large number of courses, exercises and simulations available to all CAF officers if fewer than 50 personnel will end up deploying to UN missions? This perspective, however, fundamentally misunderstands the purpose of military training, as well as the current political willingness to re-engage in PSOs. The aim of training regimes is not just to address the operational requirements of yesterday, but to ensure that military members are prepared for a wide range of possible operations that the Forces will be asked to engage with in the future.

While the Harper government has, over the last 10 to 15 years, resisted significant contributions to UN peacekeeping operations, it is certain that under the Trudeau government, the Forces will be asked to send more personnel to peace operations. Indeed, the government’s 2015 Throne Speech states a plan to “renew Canada’s commitment to United Nations peacekeeping operations.”33By cutting its activities dedicated to peacekeeping to less than half, the CAF has significantly reduced its flexibility and preparedness in this domain and runs the risk of being less than able to follow the Government of Canada’s current and future directions.

Indeed, the loss of CAF experience in the field since the early 2000s has carried a high price. The Canadian Forces, which once deployed in large numbers, now has little peacekeeping experience on which to base any contributions to UN PKOs (or international training). The methods, standards, numbers and doctrines of the United Nations have all evolved considerably over the past decade as the UN experienced the two surges (see Figure 2 but Canada has not kept up.

The United States is putting renewed emphasis on UN peacekeeping and is urging countries from both the developed and developing worlds to contribute more. One New York Times headline highlighted an initiative of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff: “Top American Commander Warns U.N. That Too Few Carry Efforts for Peace.”34 Furthermore, President Barack Obama led a Leaders’ Summit on Peacekeeping in New York on 28 September 2015 to shore up trained personnel and equipment contributions to meet the UN’s demanding mandates. Over a dozen nations pledged increased training, but the Harper government was absent from the summit altogether.35 Already some European countries are re-engaging in peacekeeping, such as France, The Netherlands and Sweden in the Mali mission. Like those countries, Canada has much to contribute, if it can properly prepare itself.

4. RECOMMENDATIONS

Peacekeeping training entails much more than unarmed combat exercises, marksmanship, and obstacle courses; on the ground, the most important talent may be walking in the shoes of the native population.… The quality you need most in United Nations peacekeeping is empathy.

– Canadian peacekeeping soldier36

Canada’s international reputation as a prolific and proficient peacekeeper has been in decline for over a decade, owing to the country’s disengagement with operations in the twenty-first century. Of parallel concern is the loss of training infrastructure, which also affects the country’s ability to re-engage with peacekeeping in the future. As the peacekeeping veterans from the 1990s retire, and as the courses and exercises that were developed to prepare officers for the unique challenges of peacekeeping deployment are cut, Canada’s future foreign policy options have narrowed.

Modern PSOs have challenging mandates and operate in dangerous environments, under the operational control of a United Nations that has significantly evolved. The Office of Military Affairs with the Department of Peacekeeping Operations grew to 20 times the original size since its creation in the 1990s. Future Canadian peacekeepers must know about the UN system, its field structures, its limitations and capabilities (e.g., in command and control, and intelligence), its procurement processes, the capabilities of other troop-contributing contingents, the peacekeeping partners (e.g., NGOs) and interactions with host state armies, police and bureaucracies. Peacekeeping courses should emphasize the differences from NATO operations, pointing out that UN operations are headed by a civilian (the Special Representative of the Secretary-General) and are integrated civilian-military operations. Training as such should cover many more potential scenarios than in traditional peacekeeping. Soldiers need to manage critical incidents, defuse potentially violent escalations, and engage in conflict resolution – not easy tasks. It requires the “soldier-diplomat” to stop people from fighting. When former friends, neighbours and ethnic groups are coming to blows and engaging in ethnic cleansing, the peacekeeper must practise interpositioning, disarm unwilling factions, carry out arrest operations for war criminals and work with the nation-building elements of the international community. To meet this challenge, advanced training needs to be developed. The following recommendations would be important first steps in establishing such advanced training:

Recommendation 1: Revive selected peacekeeping courses and exercises that were abandoned. Many of the excellent courses and exercises are still relevant and could easily be revived at minimal cost. The expertise in peacekeeping training that has been painstakingly developed need not be lost. While peacekeeping has evolved, many of the principles and practices have remained the same and can be built upon.

Recommendation 2: Develop new training materials and mechanisms. Modern peacekeepers face significantly more dangerous environments and challenging mandates than in the traditional peacekeeping that Canada led in the Cold War. New operations also have more advanced doctrine, tools and technologies to work with. New training materials are therefore needed, particularly for the robust peacekeeping of today.

Recommendation 3: Develop a new peacekeeping training centre. The loss of the Pearson Peacekeeping Centre was a devastating setback to Canadian preparedness; its revival (under that name or another) would help put Canada back in the game, when other countries like the United States, Europe and many developing countries have surpassed Canada’s early lead. Canada should work with these countries and the International Association of Peacekeeping Training Centres, which was founded at the PPC in 1995, to make a solid contribution to international training. Some of the training tools and exercises developed in other countries could be integrated so that CAF members could benefit from the experience of other peacekeeping contributors and become more interoperable with them.

Recommendation 4: Integrate preparation for peace operations into the institutional culture of the Canadian Forces. It is often said that Generals tend to fight the last war. To ensure that the Canadian Armed Forces are not training only for Afghanistan-style missions, a renewed culture of preparation needs to be cultivated, for UN operations as well as others. Indeed, modern peacekeeping training might have helped Canada understand the lessons of the US-led Afghanistan military mission.

Recommendation 5: At a more tactical level, training materials should include a wide range of topics. The following should be included:

– UN roles, e.g., nation-building/elections/prevention/protection of civilians

– UN organization, including command and control (C2) measures and civil-military cooperation

– UN doctrine and operating techniques, tactics and procedures

– The roles of other UN components and actors, especially those of UN police and human rights officers

– Non-UN partners, such as local governments and regional powers

– “Humanitarian space” and NGOs, including direct exposure to active field organizations

– History/experiences/lessons in peace operations and in host states

– Political/diplomatic roles

– Negotiation and mediation between conflicting parties

– Peace processes

– De-escalation techniques, including those for firefights and inter-group conflict

– Protection of civilians

– Dealing with sexual exploitation and abuse

– Host state, including human rights violations committed by it

– Transition to a peace-building mission

– Pre- and post-deployment resiliency training, including mitigation of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder.

In 1997, the government inquiry into the Somalia Affair decried the state of peacekeeping training in the Canadian Forces, drawing a direct link between inadequate training and the debacle in Somalia. Almost 20 years later, it is essential that we heed the lessons of that experience:

A much wider array of knowledge and skill is required (for peacekeeping operations) than is normally covered under General Purpose Combat Training. Broadening the knowledge and skill base through education and training is also a way of shaping appropriate attitudes and setting the right expectations to help CF members adapt to the demands of traditional peacekeeping or other peace support missions.37

In July 2015, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff of the US military made a strong case for further involvement in peace operations to the international community:

Ultimately, the [peacekeeping] missions we collectively support serve a most noble cause – the greater good of humanity and protecting those who do not have the means nor the strength to protect themselves. We stand together in peacekeeping for the simple reason that it’s the right thing to do.38

Re-engaging in peace operations is not merely altruism, it is enlightened national interest. In its first Speech from the Throne, the Trudeau government made the commitment: “to contribute to greater peace throughout the world, the Government will renew Canada’s commitment to United Nations peacekeeping operations ….”39 More specifically in the Mandate letter to the Minister of National Defence, Prime Minister Trudeau asked the minister to “[lead] an international effort to improve and expand the training of military and civilian personnel deployed on peace operations.”40 This will necessitate improved training within Canada.

Annex 1. Royal Military College (RMC): Undergraduate and Graduate Courses

This comparison between 2014/15 and other years includes both undergraduate and graduate courses, as listed and described in the RMC Calendars. It uses the RMC counting of credits: one term course receives one credit; and full-year (two-term) course receives two credits. It does not include the peacekeeping summer institutes that were co-sponsored by RMC in 2001, 2002 and 2004.

Overview of credits (counting residential and distance learning credits):

2014/15: 2 res + 4 DL = 6 credits

2011/12: 6 res + 2 DL = 8 credits

2005/06: 5 res + 2 DL = 7 credits

2001/02: 4 res + 2 DL = 6 credits

Academic Year 2014/15

| Course Code | Course Name | Course Description |

| HIE 380 (History; 2 credits; equiv. to POE210+ POE324 (IOs)) |

Peacekeeping & Peacemaking | A study of peacekeeping and peacemaking operations in the 20th century from the Boxer Intervention of 1900 to the present. Operations taken under the auspices of the League of Nations and the United Nations will be analyzed as well as those endeavors involving cooperation between alliance or coalition partners. Special attention will be paid to the roles and the missions undertaken by the Canadian Armed Forces in the post-1945 era. |

| HIE 382 (1 credit; DL; not offered 2014/15; exclusion POE410) |

An Introduction to Issues in Peacekeeping and Peacemaking | A survey of selected issues in the history of peacekeeping and peacemaking in the late 20th Century. The issues covered will include: the evolving theory of peacemaking, humanity and warfare, disarmament, war crime trials and international law, the United Nations, civil-military co-operation in peacekeeping, international alliances and peacemaking. Attention will be paid to Canadian military, diplomatic and civilian contributions to the development of peacekeeping. |

| POE 210 (Politics, 1 credit; DL) |

Introduction to Peacekeeping | This course is designed to introduce students to the wide range of activities referred to as peacekeeping. The history of peacekeeping is reviewed through a series of case studies to better understand the evolution of contemporary peace support operations. This course provides an analysis of the consequences of peacekeeping and the emerging trends in the field, including gender and peacekeeping, HIV/AIDS and peacekeeping, and the impact of non-state actors on peacekeeping. |

| POE 410 (1 credit; DL; exclusion HIE380) |

International Conflict Management | This course introduces students to the evolution of international peacekeeping, and the theory of third party intervention as a mechanism for managing armed conflicts. Students are introduced to a range of activities from 19th Century imperial policing and small wars to League of Nations Mandates, peace observation, and the UN system. The practice of peacekeeping is reviewed through a series of case studies as a background for introducing students to contemporary peace support operations and the evolving nature of the mandates and requisite activities that make up international peacekeeping efforts. |

| DM/MPA 567 (Security & Defence Management & Policy / Master of Public Admin.; 1 credit, DL) |

Managing and Resolving Violent Conflicts | This course examines the causes and correlates of violent conflict, and applies this to the study of conflict resolution before, during and after armed and organised violence within and between states. The evolution of conflict resolution as a discipline from the 1950s to the present, and changingpatterns of violence in the 20th century highlight third party roles and coercive and collaborative strategies. These themes are then explored through three phases in the conflict cycle: prevalence, violence, and post-violence. Comparative case studies of prevention, management, and post- conflict reconstruction are drawn from post-Cold War conflicts. The course assumes knowledge of basic conflict analysis tools and vocabulary, and requires wide reading about contemporary conflicts. It is strongly recommended that DM565 Conflict Analysis and Management be taken before this course. |

| WS 509 (War Studies; 1 credit) (not offered 2014/15 but listed in calendar) |

Evolution and Theory of International Peacekeeping | This course examines the evolution of international peacekeeping, and the theory of third party intervention as a mechanism for conflict management. The evolution of interventions is traced from 19th century imperial policing and small wars to League of Nations Mandates, peace observation, and the UN system. Conflict resolution theory has some impact on peacekeeping after 1956, and new forms of post-colonial peacekeeping and stabilization missions characterize the Cold War period. These are examined from an interdisciplinary perspective. |

| WS 511 (1 Credit, DL) |

Contemporary Peace and Stabilisation Operations | This course considers peacekeeping and international stabilization operations since the 1980s, with a focus on operations mounted by the UN and regional organizations. The political, strategic and tactical dimensions of peacekeeping are considered, drawing on the academic disciplines of history, political science, and social psychology. The course reviews efforts to improve and reform the conduct of international peacekeeping in light of recent experience, and the normative biases of peace studies, conflict resolution, and strategic studies. |

2014/15 Credits (Summary)

Undergrad: 2 res (HIE380) + 0 DL

Grad: 0 res + 4 DL (POE210, POE410, MPA567, WS511)

Total: 2 res + 4 DL = 6 Credits

Academic Year 2005/06

| HIE 380 (2 Credits) |

Peacekeeping & Peacemaking | As previously indicated. |

| HIE 382 (1 Credit; DL through DCS) |

An Introduction to Issues in Peacekeeping and Peacemaking | As previously indicated. |

| POE 210 (1 Credit; DL through DCS) |

Introduction to Peacekeeping | As previously indicated. |

| DM 567 (1 Credit) |

Managing and Resolving Violent Conflicts | As previously indicated. |

| WS 509 (1 Credit) |

Evolution and Theory of International Peacekeeping | As previously indicated. |

| WS 511 (1 Credit) |

Contemporary Peace and Stabilisation Operations | As previously indicated. |

(POE 410 not offered)

2005/06 Credits (Summary):

Undergrad: 2 res (HIE380) + 2 DL (HIE382; POE210)

Grad: 3 res (DM567; WS509; WS511) + 0 DL

Total: 5 res + 2 DL = 7 credits

Academic Year 2001/02

| HIE 380 (2 credits) |

Peacekeeping & Peacemaking | As previously indicated. |

| HIE 382 (1 credit; DL) |

An Introduction to Issues in Peacekeeping and Peacemaking | As previously indicated. |

| POE 110 (1 credit; DL) |

Introduction to Modern Peacekeeping | A description was not provided in the calendar. Calendar refers to Division of Continuous Studies (DCS) for further information. From Course Notes Preface: POE 110 is a one-semester (15-week) course offered through the Division of Continuing Studies. The course provides an introduction to peacekeeping within the disciplines of conflict studies/management, international relations, history, and social psychology. It analyzes the study of conflict itself and surveys the UN system as a vehicle for managing conflict within and between states. It examines historical patterns in peacekeeping as a means to enhance diplomacy, suppress violence, reduce suffering, manage transitions, and impose order. Drawing on an interdisciplinary approach that involves social psychology, it also explores issues related to cross-cultural communication and conflict resolution in protracted social conflicts. The course is designed to prepare students for subsequent courses in conflict studies/management, international relations, history, and social psychology by introducing central concepts in each discipline, and illustrating how they are relevant to an interdisciplinary study of peacekeeping. Peacekeeping cases will be analyzed to facilitate an understanding of the evolution of peacekeeping and to examine lessons learned as they apply to modern peacekeeping. |

| WS 508 (2 credits) |

International Peacekeeping | The course examines the evolution of international peacekeeping with an emphasis on the role of the United Nations and other multilateral organizations. The political, strategic and tactical dimensions of peacekeeping are covered. The course reviews efforts to improve and reform the conduct of international peacekeeping in light of recent experience. |

2001/02 Credits (Summary)

Undergrad: 2 res (HIE380) + 2 DL (HIE382; POE110)

Grad: 2 res (WS508) + 0 DL

Total: 4 res + 2 DL = 6 Credits

Sources: Royal Military College Undergraduate and Graduate Calendars, e.g., current calendars available at https://www.rmcc-cmrc.ca/en/registrars-office/undergraduate-calendar-2015-2016 and https://www.rmcc-cmrc.ca/en/registrars-office/graduate-studies-calendar

Annex 2. Canadian Forces College (CFC): Joint Command and Staff Level

Lists PSO-related activities in the Joint Command and Staff Programme (JCSP) and its predecessors (Command and Staff Course or CSC) held at the CFC.

Other acronyms: Lectures (LE); Discussions (DI); Tutorials (TUT); Seminars (SM); Electives (ELE)

Lecture-Discussions.

In-Class Activities

|

Academic Year |

PSO Activities |

Number |

Contact hours |

|

2015/16 |

The United Nations (LE) The Evolution of PSOs |

Lectures: 3 Discussions: 0 Tutorials: 0 Seminars: 0 Electives: 1 Lecture-Discussions: 0 |

4.5 hours (for all students) 1 elective (12 3-hr classes) for 16 students |

|

2014/2015 (JCSP 41) |

The United Nations (LE) The Evolution of Peace and Stability Operations (LE) [AJWS Stream] |

Lectures: 2 Discussions: 0 Tutorials: 0 Seminars: 0 Electives: 0 Lecture-Discussions: 0 |

1.5 hours (for all students) (Additional 1.5 hours for AJWS stream, i.e. approx. 1/3 of JCSP students) |

|

2013/2014 (JCSP 40) |

The Evolution of Peace and Stability Operations (LE) [AJWS] The United Nations Structures and Procedures (SM) [AJWS] The UN in Haiti: A Case Study (SM) [AJWS] The UN in the DRC: A Case Study (SM) [AJWS] |

Lectures: 1 Discussions: 0 Tutorials: 0 Seminars: 3 Electives: 0 Lecture-Discussions: 0 |

4.5 hours (all students) 10.5 hours (for AJWS stream) |

|

2012/2013 |

Stability Operations (LE) PSOs (DI) Peace and Stability Operations: An Evolving Practice (ELE) The United Nations (LE) |

Lectures: 2 Discussions: 1 Tutorials: 0 Seminars: 0 Electives: 1 Lecture-Discussions: 0 |

6 hours (all students) 1 elective (30 contact hours for 10-15 students) |

|

2011/2012 (JCSP 38) |

Stability Operations (LE) PSOs (DI) Peace and Stability Operations: An Evolving Practice (ELE) The United Nations (LE) |

Lectures: 2 Discussions: 1 Tutorials: 0 Seminars: 0 Electives: 1 Lecture-Discussions: 0 |

6 hours 1 elective (30 contact hours for 10-15 students) |

|

2010/2011 (JCSP 37) |

Stability Operations (LE) PSOs (DI) Peace and Stability Operations: An Evolving Practice (ELE) The United Nations (LE) |

Lectures: 2 Discussions: 1 Tutorials: 0 Seminars: 0 Electives: 1 Lecture-Discussions: 0 |

6 hours 1 elective (30 contact hours for 10-15 students) |

|

2009/2010 (JCSP 36) |

PSOs (DI) Stability Operations (LE) The United Nations (LE) |

Lectures: 2 Discussions: 1 Tutorials: 1 Seminars: 0 Electives: 0 Lecture-Discussions: 0 |

6 hours |

|

2008/2009 (JCSP 35) |

PSOs (DI) Stability Operations (LE) The UN - Canada's Ambassador's Perspective (LE) The United Nations (LD) |

Lectures: 3 Discussions: 1 Tutorials: 1 Seminars: 0 Electives: 0 Lecture-Discussions: 1 |

7.5 hours |

|

2007/2008 (JCSP 34) |