EAST TIMOR 1999: Experiences as a UN Electoral Oficer

Writings

– East Timor: Personal Encounters with Militias (Peace Magazine)

– Tribute of a Timor Lover (poetry)

PowerPoint Presentations

– UN Electoral Operations: Case Study East Timor 1999 (pdf, 1.6 MB)

Photos

In the summer of 1999, I served as a UN electoral officer in East Timor, the half-island occupied by Indonesia. I was part of the United Nations Mission in East Timor (UNAMET) whose mission was to administer a free and fair referendum so the Timorese people could choose their future: integration with Indonesia or independence. After a few days of pre-deployment training by UN staff stationed in Darwin, I was sent to Timor aboard a Hercules aircraft provided by South Africa.

Here is my first view of the enchanting island of Timor in June 1999:

My view out the small round Herc window of Dili, the capital.

Before landing, we were told to be prepared for press photographers on the runway. There were none, so we did the next best thing ... we took pictures of ourselves!

Here is a fellow electoral officer, the Liberian gentleman Gongolo, who posed for this photo before we entered the Dili Airport building. The inspiring banner reads "WELCOME. If you love East Timorese, LOVE BOTH the pro integration and the pro independence." Gongolo later became a member of my electoral team.

Then we were sent to our region (Suai, which borders West Timor) aboard Puma helicopters.

At the Suai headquarters, I was assigned a police officer from Malaysia. That was quite handy since his language (Bahasa Malaysia) was very close to Bahasa Indonesia, which was widely spoken in East Timor (along with local languages, especially Tetun)

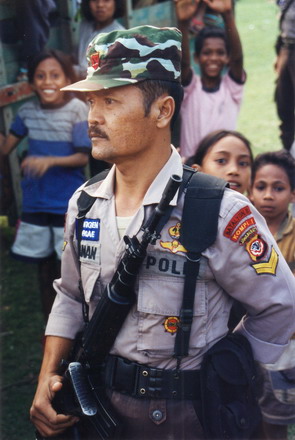

The Indonesian police were to escort us "for our security" but we felt their main job was to make sure that we didn't do anything "improper," and to keep an eye on us. It also promoted the charade that Indonesia was the protector of the Timorese people, when in fact it was an oppressor.

Here's one of my teams in blue, along with the Indonesian soldiers assigned to escort us on one particular trip. The driver is squatting and one of my translators is on the far right.

Some scenery from one of many trips.

Some beautiful scenes ...

Always enjoyed seeing the children of Timor. The two shown here are in school uniforms bearing the Indonesian colours.

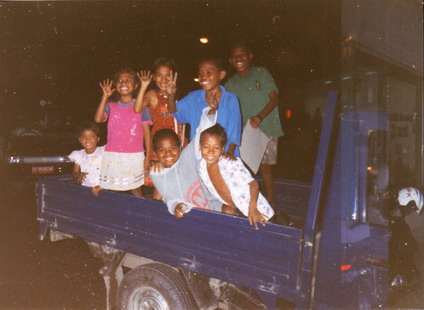

Children were also a joy to hear ... "Hello Meester" they would shout while waving and smiling.

Visiting a village near Suai, I spoke with the elders. When I asked how the crop was going that year, the man without a shirt told me that they had not planted seeds that year. I was surprised because the people were subsistence farmers. Without a crop they might starve! He said that if they planted the militiamen would come and take the crop by force, so they decided not to plant!

The UNAMET mission had 500 electoral officers and only 50 military advisers (all unarmed). Below you see four of them. In this photo, I also managed to capture the profile (right) of a notorious militia leader. At one point, his militiamen threatened that "my security and that of my team could not be guaranteed." I was called a "spy." (For whom, they did not say.) A few days later, the Irish colonel (second from the right of the four) convinced the Indonesian military to tell the militia leader to withdraw the threat. I was much relieved when the militia leader said it had been a "mistake." I was not a spy after all!

In the town of Zumalai, the church was boarded up. The priest, Padre Francisco, had been told by the local militia that if he preached any more there, he would be killed. So he took refuge in the Suai church complex.

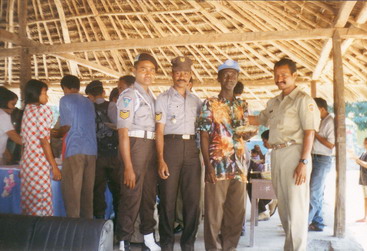

Here is Gongolo with some Indonesian soldiers and a militia leader (far right).

Indonesian police, which only a year or two before had been separated from the military ...

Entrance to a military base. I took a little risk to take this picture ...

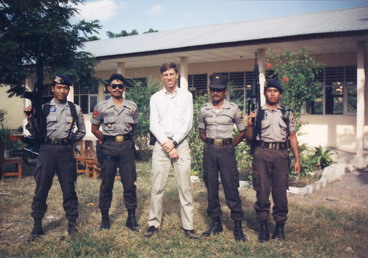

Myself with some junior Indonesian soldiers:

The militia parading through the streets of Suai to show their support for "integrasi" (integration with Indonesia).

The militia in and around Zumalai was named MAHIDI, said to stand for "Integration dead or alive!"

After the people rejected integration and voted 78% for independence, as announced by the UN on September 6, the militia took their revenge. They burned 90% of the building in the capital, including these ones.

Fortunately, the Australian-led international force INTERFET was permitted entry, after the US (Pres. Clinton) and the international community put heavy pressure on Indonesia. Only a thousand lives were lost. Unfortunately it included 200 civilians who were slaughtered in the Suai Church complex. Among the dead was a member of my team, Frederico, who had taken refuge at the church after militiamen saw him informing me of their attempts to falsely register. Padre Francisco was shot in cold blood as he pleaded for the parishioners in the church, who were also murdered.

Below is an image I I took this image from a UN helicopter in July. It shows the Suai church complex, including the Ave Maria church (top left) and the unfinished cathedral (centre) that Indonesia had begun to build but stopped when the referendum process had begun. The Indonesians claimed to have built more churches in East Timor (Timor Timur or TimTim, as they called their 27th province) during their 24 years there than the Portuguese had in almost four centuries of colonialism there.

The cathedral viewed from the grounds of the associated school:

Some IDPs (internally displaced persons) made their home inside the roofless cathedral structure after they had to leave for villages because they were deemed pro-independence by the militia.

Many live in tents made from tarps given by UN relief agencies.

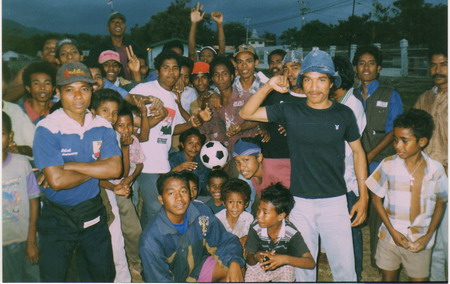

After playing soccer with the kids, I took their picture. The young man in black is giving the fisted salute of FALANTIL, the rebel force.

The late Padre Francisco:

Voter education was part of the UN mission. I spoke to some 700 Timorese after a mass at the Ave Maria Church. I said that their individual votes would be secret (something new for them) and that no matter what the outcome of the "popular consultation" (referendum), the UN would not leave Timor.

But shortly after the "reign of terror" started on 6 September 1999, the UN evacuated all its person (except a dozen uniformed personnel holed up the Australian consulate in Dili). Back in North America, I could not help but feel that I had betrayed the people in Suai who were massacred without UN protection. Take God, about 10 days later, the Australian-led force entered to establish peace and oversee the Indonesian withdrawal. The United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor (UNTAET) took over governance of the half-island for almost two years before handing over the reins to officials who won the UN-run elections. Here is a banner flying outside the location of some killings in Dili:

Before I left in August, I had promised my Timorese friends of team members that I would return. I kept that promise in 2001. Here I am with the family of my translator Teresa Immaculada Galhos, who several years later got a university education in Australia, married an Australian, and now has a child of her own.

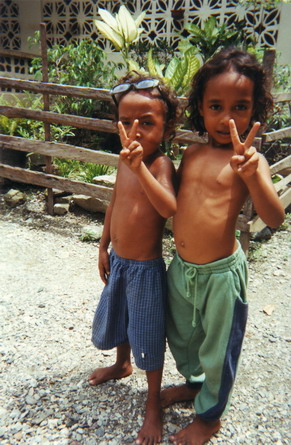

Two young members of the extended family giving me the peace sign:

For those who have known oppression and war, the message above the licence plate on this truck in Suai is particularly poignant.

One of my favourite photos from the UN deployment in 2000 (after the Timor tragedy) can be found here.

My feelings about Timor are best expressed in poetry: Tribute of a Timor Lover.