TRACKING THE PROMISES:

Canada's Contributions to UN Peacekeeping

Dr. Walter Dorn, 4 October 2025

Using UN monthly data from 31 July 2025

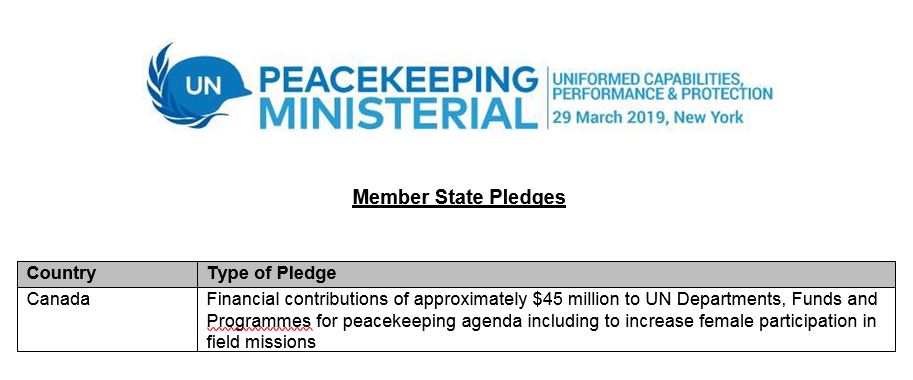

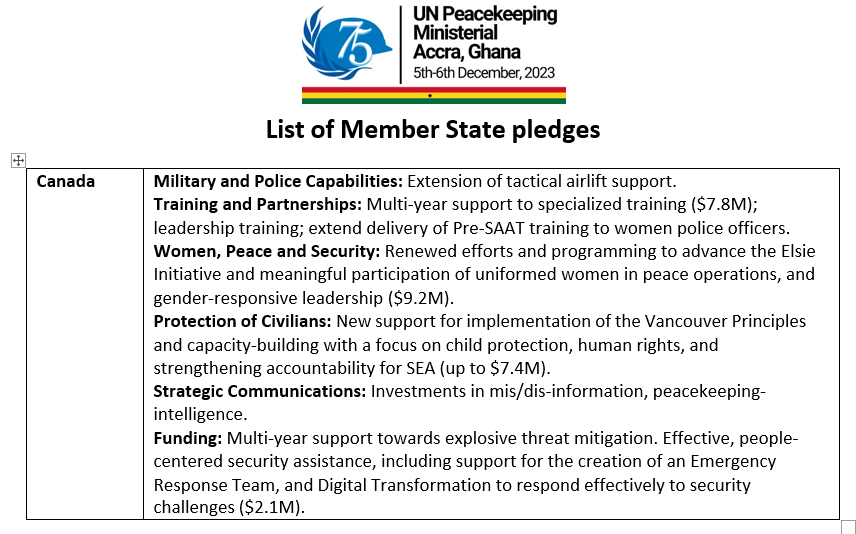

Canada has pledged to the United Nations and to the international community to provide substantial contributions to UN peacekeeping. Specifically, major pledges were made at the Peacekeeping Ministerials in London 2016 (pdf) and Vancouver 2017 (pledges), and lesser pledges in ministerials in New York 2019, Seoul 2021, Accra 2023, and Berlin 2025. To what extent have the significant pledges been fulfilled?

This webpage tracks the status of implementation of these government promises on UN peacekeeping using easily measurable statistics, the latest figures, historical data, commentary, and comparisons to benchmark data for key commitments. It draws conclusions for each area of potential contribution and conclusions overall.

CONTENTS

Latest stats

Uniformed Personnel

Women in Peacekeeping

Uniformed Personnel at UN Headquarters

Leadership

Services

Financial

Training for UN Operations

Intellectual/Political/Policy Contributions

CONCLUSION (Overall)

References

Annexes

Canada's Personnel Contributions to UN Peace Operations as of 31 July 2025:

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Police | 4 | 4 | 8 |

| Mil | 6 | 0 | 6 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 10 | 0 | 10 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Mil | 22 | 1 | 23 | ||

| Police | 5 | 4 | 9 | ||

| Totals | 27 | 5 | 32 |

Source: UN

Pledge: Up to 750 uniformed personnel, i.e., 600 military + 150 police (2016 London Ministerial: pdf). This should be in addition to what Canada deployed at the time, 112, as is required for the pledging conference (i.e., pledging new contributions only). So the total would be approximately 860.

Status: 32 Canadian uniformed personnel deployed, according to UN figures.

Table 1. Number of Canadian uniformed personnel, key historical points and last UN report

| Date | Military | Police | Total | Source | Comment |

| 1993 Apr 30 | 3,291 | 45 | 3,336 | UN, 1993 | High point, with deployments in Bosnia, Cambodia, Cyprus, and Somalia |

| 2015 Oct 31 | 27 | 89 | 116 | UN, 2015 (pdf) | Conservative gov, last official figures |

| 2016 Aug 31 | 28 | 84 | 112 | UN, 2016 (pdf) |

Contribution when London |

| 2017 Oct 31 | 23 |

39 |

62 |

UN, 2017 (pdf) |

At time of Vancouver Ministerial, last official figures beforehand |

| 2018 May 31 | 19 | 21 | 40 | UN, 2018 (pdf) |

Up to that date, lowest number of uniformed personnel -- lowest military contribution since 1956; lowest police contribution since 1992 |

| 2019 Feb 28 | 167 | 23 | 167 | UN, 2019 (pdf) | Highest contribution from Trudeau gov, with Mali mission, with national support element (NSE), total is about 250 military |

| 2020 Aug 31 | 22 | 12 | 34 | UN, 2020 (pdf) | Up to that date, lowest number of uniformed personnel since 1956 and lowest police contribution since 1992 |

| 2024 July 31 | 17 | 9 | 26 | UN, 2024 | Lowest number of uniformed personnel since 1956 |

|

2024 Dec 31 |

21 | 5 | 26 | UN, 2024 |

Last UN stats from Trudeau's term as Prime Minister; tied for Lowest number of uniformed personnel since 1956 |

| 2025 July 31 | 23 | 9 | 32 | UN, 2025 |

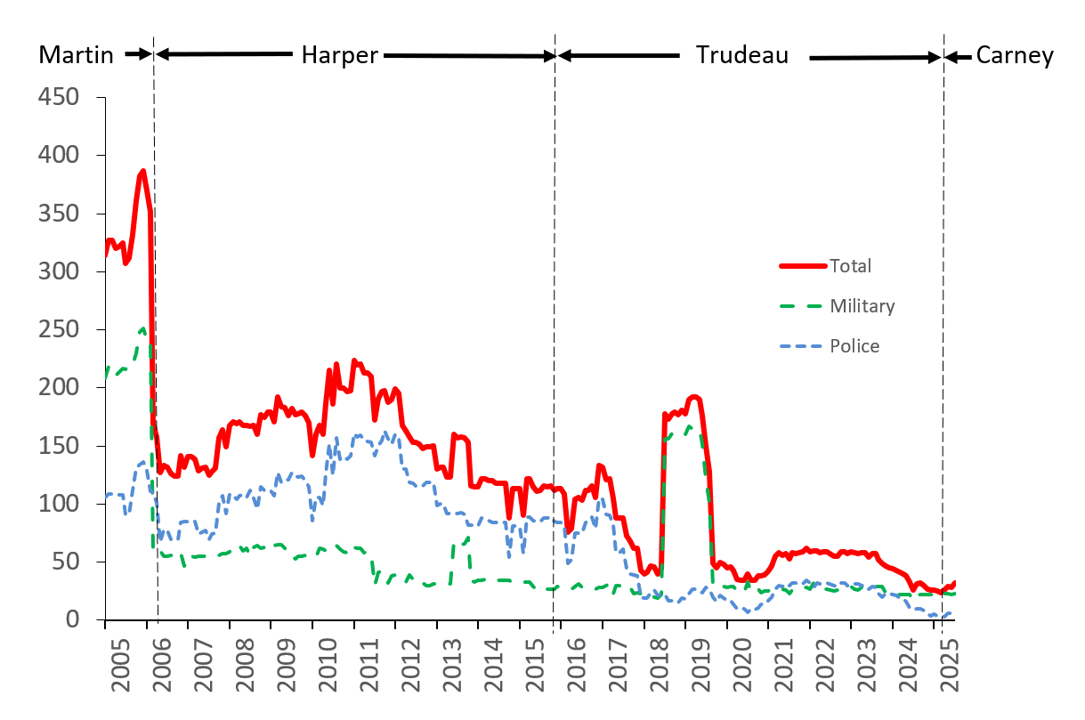

Figure 1. Contribution by month, from 2005 to 2025, showing governments in power at the time

Historical benchmarks:

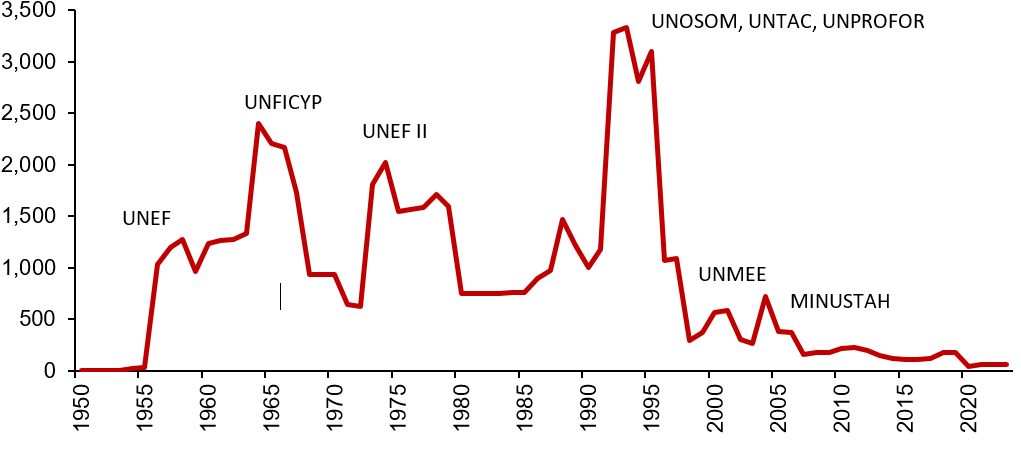

Canada was a leader in providing personnel to UN peacekeeping from the early days, e.g., providing the first military observer chief, BGen Harry Angle, to UNMOGIP, which was the first UN observer mission, created in April 1948 for Kashmir. In 1956, Canada proposed the first peacekeeping force, UNEF in Suez/Sinai, and made major contributions, including battalion-sized contributions throughout the life of the mission (1956–67). It also helped create the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), to which Canada contributed large units (battalions) for about 30 years (1964–1993).

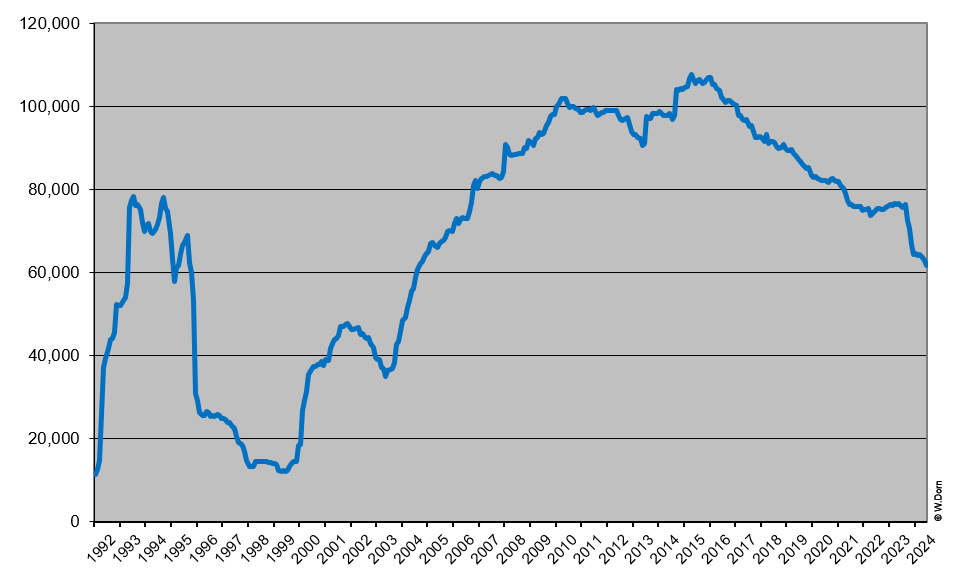

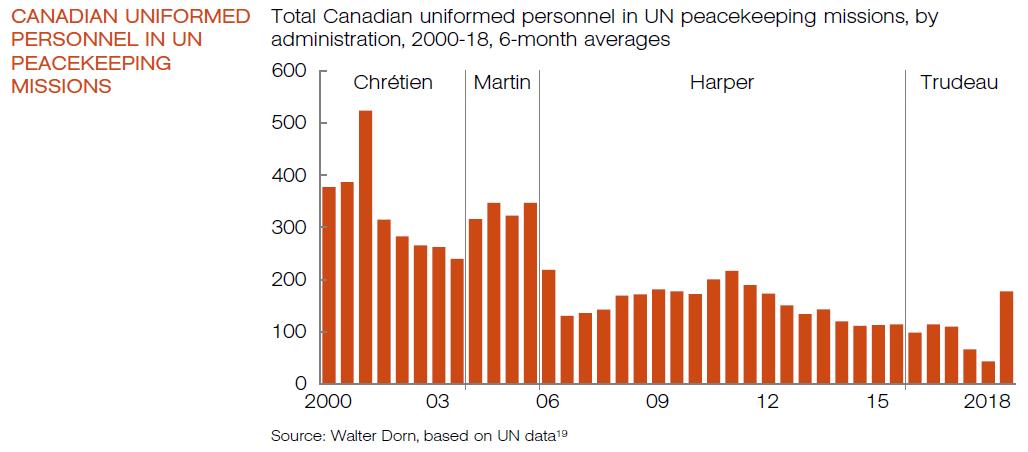

Canada was the only country to contribute to ALL peacekeeping operations during the Cold War, with about 1,000 deployed on monthly average for 40 years. It remained a top contributor into the early 1990s. In 1993, Canada had 3,300 uniformed personnel deployed in UN missions (including in Bosnia, Cambodia, Mozambique, and Somalia; in Somalia, Canadian soldiers also served in a non-UN US-led mission UNITAF, under which several Canadian soldiers committed war crimes). Canada contributed approx. 200 logisticians to the UN Disengagement Observer Force in Golan Heights (UNDOF, in Syria) from its creation in 1974 until 2006, when the Harper government withdrew them (see decline in Figure 1). So during the half-century 1956–2006, Canada always maintained at least 500 uniformed personnel in peacekeeping. For forty years Canada contributed about 1,000 or more (see Figure A2 in Annex below). Numbers fall in 1997 and in March 2006, shortly after the Harper government came to power, the UN contribution dropped to 120 personnel.

When President Barak Obama co-hosted the Leaders' Summit on Peacekeeping at UN headquarters on 28 September 2015, Canada made no pledge. That same night, in an election debate, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau criticised the government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, saying:

The fact that Canada has nothing to contribute to that conversation today is disappointing because this is something that a Canadian Prime Minister started, and right now there is a need to revitalize and refocus and support peacekeeping operations.

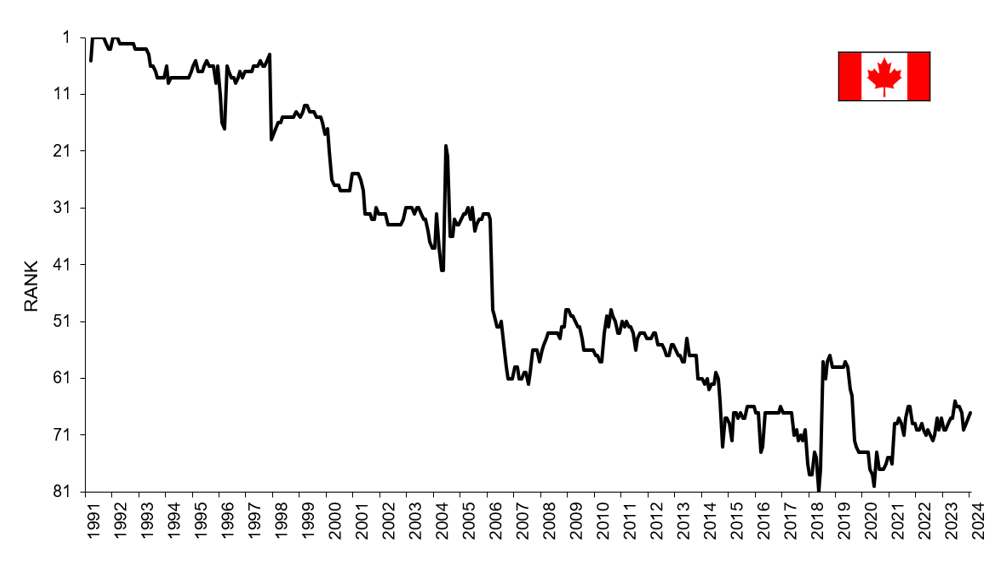

Before his election in October 2015, Trudeau criticized the Conservative government of Stephen Harper for a decline in the number of uniformed personnel (rank 66th on the list of contributors on 30 September 2015). Surprisingly, under the Trudeau government, the contribution fall further for over two years until Canada reached its lowest rank in history: 81st (31 May 2018). The rank increased substantially in July 2018 with the addition of 134 mil personnel in Mali (as counted by the UN) but that was short lived. By 2020, it reached its lowest point ever: just 34 personnel.

During the one year deployment in Mali (2018-19), the Canadian defence department (DND) frequently stated that the number deployed in Mali is "approximately 250 personnel." The discrepancy between UN and Canadian statistics arises because Canada generously deployed more personnel on this mission than the UN pays for. (The UN has standards for the number of deployed for a given function like aviation support that are much lower than what Canada deemed was required for its deployment.) So the additional Canadian personnel (approx. 100) were considered part of a "National Support Element" (NSE), which is not reimbursed, though most of these personnel still wore UN insignia and were incorporated into the mission as part of the regular UN chain of command.

The Mali contribution was the largest Canadian deployment since 2005 and only the third time it contributed a military unit since 2005 (both other units were short one-time deployments in Haiti with no rotations). With the Mali deployment, the number of uniformed personnel deployed finally became greater than what it was when the Harper government ended in October 2015. But instead of reaching the promised level of 860, Canada never contributed over 300. Following the Defence and Foreign Ministers' announcement on 19 March 2018 that Canada will contribute to the UN mission in Mali, Canada provided an aviation task force of 8 helicopters (three Chinooks and five Griffons). This was a substantial military contribution with high quality assets, though of low risk. The initial Vancouver pledge was made by the PM as a "smart pledge," (video)(text), which means "helping [the UN] to eliminate critical gaps" by securing successive rotational contributions from different countries but Canada still left a gap until the next country (Romania) took over the responsibility in mid-October 2019. So the pledge was not so "smart." Furthermore, the police contribution reached the lowest point since 1992 (just 15 police officers in November 2018, see Figure 1). At less than 20 officers, this is lower than any point in the Harper government, though the authorized ceiling under the Trudeau government is much higher at 150 overall, with 20 authorized for UN mission in Mali, and 35 for the mission in Haiti; see RCMP current operations).

Conclusion:

– Canadian personnel contributions sunk to a record low in 2024. Not since Canada proposed the first peacekeeping force in 1956 had Canada made a smaller contribution of personnel.

– More than a half-decade after the 2015 Liberal campaign pledge, the personnel promises ring hollow. Only one substantive increase over the Harper monthly numbers was made, but for only for one mission (Mali) for a short duration (one year). The UN's request to extend the critical CASEVAC (casualty evacuation) capability until 15 October 2019 was denied by Canada (DND, "UN Request," 2019), leaving the UN with a major vulnerability.

– The average number of deployed uniformed personnel under the Trudeau government (monthly average of 81 personnel from 2015 to 2024) is about HALF that of the Harper government (157). The number of police deployed is 66% LESS.

WOMEN IN PEACEKEEPING^

Promise: to promote women in peacekeeping. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said at the 2017 Vancouver Peacekeeping Ministerial: "We are equally committed to increasing the number of women that we deploy as part of UN peace operations." ("Canada to deploy more women to peacekeeping missions, says Trudeau" Youtube, 1:13). A specific programme was also announced "titled Women in Peace Operations Pilot – 'The Elsie initiative.'"

Table 2. Number of Canadian uniformed women in peacekeeping (benchmark data and the recent figures)

| Date | Military Women |

Police Women |

Total |

Source |

Comment | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2015 Oct 31 | 1 | 20 | 21 | UN, 2015 (pdf) |

Conservative gov, last official figures. |

||||||||||||||||||

| 2016 Aug 31 | 2 | 13 | 15 | UN, 2016 (pdf) | At time of London ministerial, last official figures before meeting | ||||||||||||||||||

| 2017 Oct 31 | 2 | 6 | 8 | UN, 2017 (pdf) | At time of Vancouver Ministerial, last official figures before meeting |

||||||||||||||||||

| 2024 Dec 31 | 1 | 2 | 3 | UN, 2024 | Mil: 1 women of 20 (5%) Pol: 2 women of 5 (40%) To: 3 women of 26 (12%) |

||||||||||||||||||

| 2025 July 31 | 1 | 4 | 5 | UN, 2025 | Military: 1women of 22 (4%) Police: 4 women of 9 (44%) Total: 5women of 32 (16%) |

||||||||||||||||||

Recent stats:

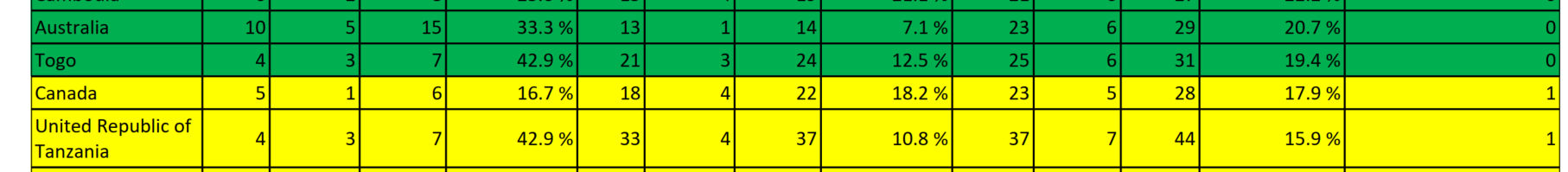

The miltiary deployed only one (1) women in July 2025. For military Staff Officers & Military Observers deployed (the only kinds that Canada currently deploys), Canada had 4% (1 in 22) female, far from meeting the UN goal of 22% for 2025. The police are closer to gender parity (44%), though the absolute number is small (4 women).

At end of December 2024, the Trudeau government provided only 3 women uniformed personnel. This is far fewer than the 21 women that the Harper government provided at the end of its term.

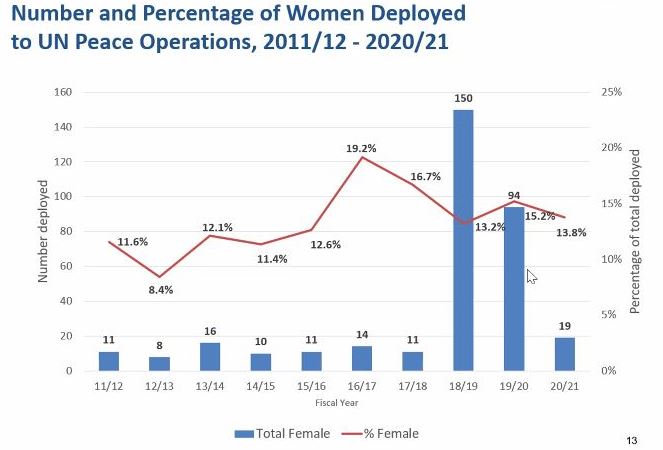

During the time of the Mali deployment (2018-19), if the National Support Element is included, the number of Canadian women increased substantially. The percentage of Canadian uniformed women on peacekeeping became especially high (25%) compared to other countries, with the UN average being (approx.) 5% for military personnel, and 10% for police. Although the UN has no target for troops, it has set a target of 16% for SOs and MILOBs in 2019 (starting 2018 at 15% and increasing 1% each year thereafter to 2028; UN Security Council resolution 2242 (2015) called for a doubling number of women by 2020).

Canada temporarily lost a military position in the UNMISS mission in March 2019 when it was unable to meet the UN standard for the percentage contribution of women as staff officers and UNMEM. After Canada pledged to increase its number of deployed women, the UN allowed Canada to retain the position.

The government's 2017/18 Progress Report on the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Agenda states: "Dedicated efforts were made to recruit women for the Canadian deployment to the UN Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), resulting in women making up 14% of the Canadian contingent, including the task force deputy commander, and to ensure gender responsive action through the deployment of a gender advisor."

The 2017/18 Progress Report also states: "Of the 45 Canadian police newly deployed to international peace operations during the fiscal year [2017/18], women made up 18%, as compared to 14% the previous year.18" [Footnote 18: "Of the total 70 police in deployment during the fiscal year, women represented on average 19% in fiscal year 2017–2018 and 18% in 2016–2017. The target is 20%, which equals the UN goal."]

Observations:

In 2020, Canada had dropped to near record lows in its contributions of women to peacekeeping, i.e., single digits. In 2024, it is only 7. But the military contribution is only one (1) women, as of 30 October 2024. In November, that fall to zero!

In 2019, Canada temporarily set a good example percentage-wise, with 19% of its UN military personnel being women, well above the UN average. For Staff Officer/MilObs deployed, Canada had 7 out of 23 or 30%, well exceeding the UN goal of 16% for 2019. The police are doing very well, having achieved close to gender parity.

In 2017, Canada's Vancouver pledge, especially the financial incentives, held promise to increase the number of women military personnel provided by other countries.

Some progress on the pledges on women, peace and security (WPS) is being made several years after the initial pledge:

– Elsie initiative: Announced at the 2017 Vancouver ministerial, the Global Elsie Fund was launched at the UN on 28 March 2019, co-organized with UN Women. The disbursements started very slowly with nothing having been distributed to participating organizations by end of 2020, three years after the announcement, and funds only going to fund administration. The programme was planned to end March 2022 before it was extended. The fund became more active with several gender gap analyses and partnerships with the armed forces of Ghana, Senegal and Zambia.

– Training assistance: two countries were designated to serve in a pilot project: Ghana and Zambia – see Freeland, Sept 2018 – (neither being Francophone), but actual training and mentoring activities did not commence in the three year period since the initiative was announced. Instead, gender gap studies were made.

– A pledge of C$21 million was made in 2017 in Vancouver for WPS in UN peace operations. This includes contributions to the UN's trust fund for victims of sexual exploitation and abuse or SEA. Whether and how those funds were actually dispersed is not known.

– More broadly, "[a] new WPS Chiefs of Defence Network was launched by Canada, the United Kingdom and Bangladesh to share best practices and compare progress in addressing barriers and challenges to integrating WPS in national militaries." Canada succeeded the United Kingdom as network chair in July 2019 (WPS CHODS website). But a planned tour of nations for WPS consultations by the chair, General Jonathan Vance, did not take place as planned.

– Canadian Gender Advisors (GENADs) were deployed with Op PRESENCE and UNMISS (South Sudan).

– Graphs of CAF women deployed by the year 2011–21 are shown in Annex Figure A.5 (below), giving the number that went on deployment each year and the percentage of women of the total deployed personnel (men and women combined).

– Percentage of women by occupation in CAF and the percentage deployed on peace ops by occupation (Annex Figure A.6) shows that women are less likely to be deployed than men in all occupations, except engineering officers.

Conclusion:

The total number of Canadian women contributing to peacekeeping has fallen drastically with the end of the Mali mission in 2019. It was only with that mission that Canada finally made an impact by example in the number and percentage (25%) of women deployed after years of slow or no progress. The percentages have since fallen, as has the number of women deployed. Some long-promised programmes are finally being implemented, especially the Elsie Global Fund, which had not dispersed funds more than three years after it was announced. The long-term effects of the Fund on number of women deployed from other nations' forces is not seen.

UNIFORMED PERSONNEL AT UN HEADQUARTERS^

Pledge: While no specific pledge has been made in this regard, service at UN headquarters provides a way to make a significant contribution, to gain Canadian experience in UN planning, procedures, and priorities, and to gain Canadian experience with the inner workings of the world organization. Positions to support UN peacekeeping should normally be in Department of Peace Operations or the Department of Operational Support. For the military, placements would usually be within the Office of Military Affairs within DPO.

Current status (military)

UN employment: 0, out of more than 120 personnel serving from over 70 countries

Gratis personnel: 1, officer of rank major serving in the UN's Conduct and Discipline Unit. Previous officers worked on issue of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (SEA).

History: Canada provided the Military Adviser to the Secretary-General or MilAd, who is head of OMA, from 1992 to 1995, namely Maurice Baril, Major-General at the time, later full general and Chief of Defence Staff. The last leadership post held by Canada in OMA was Chief, Military Planning Service: Col. Dave Barr, serving 2011–2015.

Current status of Canadian police in UN Police Division

UN employment: 0

Civilian positions: these are not contributions made by UN member states but are individually hired by the UN. However, in a major advance, Gilles Michaud, formerly with the RCMP, was appointed on 30 May 2019 as Under-Secretary-General for Safety and Security. Although the position is won on merit, it is usual for governments to support their citizens who are seeking such high-level positions. Still, it is not a secondment from the Canadian police so it is not considered a Canadian governmental contribution.

Positions at the Canadian Mission: 3 military and 1 police. The Trudeau government upgraded the rank of the Military Advisor (MilAd) in the Permanent Mission to the United Nations in New York (PRMNY) from Colonel to Brigadier-General, though the position fall back to Colonel ranks after a few years. At times in the past, the MilAd served as the "Dean" of the Military and Police Advisers Community (MPAC). The MilAd is assisted by two other military officers (usually a Lieutenant Colonel and a Major). A police advisor is also resident at the permanent mission in New York (PRMNY).

Conclusion: Canada is lagging far behind other nations at UN headquarters in an area where it once led.

LEADERSHIP^

Pledge: while no international pledge was made by Canada, the Prime Minister did request his defence minister to provide "mission commanders" for the UN. Canada has not yet done so.

Historical Background: The UN's first chief military observer, BGen Harry Angle in UNMOGIP, and the first Force Commander, MGen E.L.M. Burns in UNEF, were Canadians. Many other Canadians were appointed as UN commanders in the Cold War. Canada provided nine commanders of peacekeeping missions in the 1990s but none since. Of the nine, seven were UN force commanders and two were commanders of UN observer missions, as show in the following table:

| MGen Clive Milner | UNFICYP | 1988–92 |

| BGen Lewis MacKenzie | ONUCA | 1990–91 |

| MGen Armand Roy | MINURSO | 1991–92 |

| MGen Roméo Dalliare | UNOMUR/UNAMIR | 1993–94 |

| MGen Guy Tousignant | UNAMIR II | 1994–95 |

| LGen Maurice Baril | MNF in E.Zaire | 1996 |

| BGen Pierre Daigle | UNSMIH | 1996–97 |

| BGen Robin Gagnon | UNTMIH | 1997 |

| MGen Cam Ross | UNDOF | 1998–2000 |

Canada has not deployed any UN Force Commanders or heads of military components in the twenty-first century. Canada was offered the opportunity to submit candidates for the force commander positions in the D.R. Congo and Mali around 2008 and 2016, respectively, but did not commit. The highest ranking positions in the twenty-first century has been the Force Chief of Staff in MINUSTAH, i.e., in Haiti, 2005–2017, and Deputy Chief of Staff Operations (DCOS Ops) in MONUSCO in D.R. Congo (ongoing, as of 2024).

On the police side, a Canadian police officer headed the police component in the UN's missions in Haiti from 2004 to 2019. That has been a significant RCMP-organized police contribution.

Status: Canada lost its most significant military position in UN missions with the end of MINUSTAH in 2017. It was a colonel position as Chief of Staff. The UN mission was downgraded to a smaller mission, MINUJUSTH. However, Canada did retain the role of police (UNPOL) Commissioner in MINUJUSTH. Canada lost the major opportunity to provide the Force Commander for the Mali or MINUSMA mission in January 2017 when Canada dithered and delayed on the Mali mission, with Cabinet unable to commit. Instead, the Force Commander position in 2017 went to a Major-General Jean-Paul Deconinck of Belgium and two years later to Lieutenant-General Gyllensporre from Sweden. Canada provided a force package for Mali in 2018–19.

Aside: On the civilian side, three Canadians hold positions of mission leadership, i.e., Special Representative of the Secretary-General or SRSG: Colin Stewart led the UN mission in Western Sahara or MINURSO, since Dec 2017; Elizabeth Spehar leads the UN peacekeeping force in Cyprus or UNFICYP, since April 2016; and Deborah Lyons leads the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan or UNAMA, since March 2020. But these mission leaders are not provided by the Canadian government. These Canadians are part of the international civil service, individually recruited by the United Nations, though often with endorsement of the Government of Canada. The Canadian civilians who lead UN missions are to be much commended for their achievement and personal service.

Conclusion: In terms of providing military leadership of UN missions, this is a major failure for Canada, especially given the illustrious history of past contributions and the contributions of other middle-power nations, including Ireland and Norway, who were fellow contenders for a Security Council seat 2021-22. In early 2017, the opportunity to lead the Mali mission was missed catastrophically, causing extra hardship for the UN, with the position being unfilled for two months while the UN waited in vain for a response from Canada. In the end, Canada did not offer anyone, though the Canadian Armed Forces had chosen a general and his executive assistant (EA).

SERVICES^

Pledges: Made as part of the "Contribution of police and up to 600 military personnel" at the 2017 Vancouver commitment, "advancing" the London pledge:

Tactical Airlift Support [C130 aircraft]

Aviation Task Force

Quick Reaction Force or QRF [approx. 200 personnel]

New Police missions being examined [vague]

Status:

– The aviation task force was deployed for one year in Mali, with the aeromedical unit staying an extra month. The contribution has long passed.

– The transport aircraft unit, one CC-130 Hercules and 30-50 CAF personnel, is still being provided for UN service, based in Entebbe. It was suspended in February 2020 out of concerns about COVID-19 and Ebola. It began again in August 2020, after the agreement was signed that month to extend the mission for another year. The newer arrangement is to deploy for 15 days every 3 months instead of 5 days per month. Another extension was pledged at the December 2023 Peacekeeping Ministerial in Ghana. The tactical airlift detachment (TALDET) is providing good service to the UN.

– The plans for the deployment of a QRF, e.g., in Golan Heights with UNDOF or in Mali with MINUSMA, was being examined as a possibility in 2017 and 2018, but nothing has become of it. It currently stands as a broken promise.

Conclusion: only a fraction of the modest pledge has been fulfilled. With the Mali deployment being so short, Canada has let the UN down.

FINANCIAL^

Canada has for decades paid its UN dues "in full, on time, and without conditions," unlike countries such as the US, which regularly defaults in all three aspects – see Williams, 2018. Canada almost never misses the January deadlines for payment of its mandatory UN dues, including the peacekeeping contributions. It is 2.7% of the UN peacekeeping budget, making Canada the 9th largest contributor on the assessment scale. So Canada, under both Liberal and Conservative governments, is to be praised for this financial consistency in UN support over many decades. In addition, Canada contributed advanced helicopters to the UN mission in Mali for free, actually $1/year, while also providing some 100 personnel of the 250 at no cost to the United Nations. In this one mission, MINUSMA in Mali, Canada was quite generous, though it did not fill the time gap between its departure and the arrival of the next contingent from Romania in 2019.

In giving extra-budgetary (voluntary) funds to UN peacekeeping, Canada is a leader in the total amount, roughly $12 million per year. It supports some worthwhile projects, including the establishment of a training Joint Operations Centre or "mock JOC", with $0.5 million, in Entebbe, Uganda, to allow individuals to train on the UN's procedures, including the situational awareness programme called "UniteAware," which was piloted in the MINUSCA mission and is deployed in a few other missions (UNFICYP). In the 2021 Seoul Peacekeeping Ministerial, Minister of National Defence Anita Anand, pledged additional funds (totaling $85 million over three years) (Canada, 2021). But Canada's pledges, including in the December 2023 ministerial in Ghana, have been only funds not personnel.

Conclusion: Canada is continuing its positive record of financial contributions, though the majority of these payments are mandatory under the UN system. In peacekeeping, Canada is using dollar diplomacy not personnel contributions.

TRAINING FOR UN OPERATIONS^

Mandate Letter (2015): includes "leading an international effort to improve and expand the training of military and civilian personnel deployed on peace operations" – see full letter and subsequent letter

Pledge at Vancouver conference:

"Innovative Training"

"Training activities to meet systemic UN needs"

"Canadian Training and Advisory Team"

Status: The Canadian government is currently less well equipped to lead in training for UN peacekeeping since so few Canadian military personnel have deployed in such operations over the past two decades. In addition, the training and education within the Canadian Armed Forces on UN peacekeeping has also declined substantially, with the number of activities less than a quarter of what they were in 2005 – see study: Dorn and Libben, Preparing for Peace (2018, html or pdf) or the longer 2015 version (html, pdf). The closure of the Pearson Centre in 2013 left Canada without a place to train military, police and civilians together. The Peace Support Training Centre or PSTC in Kingston only trains military personnel and peace ops are only a small fraction of its efforts: just one course out of nine. The training is done on an individual not unit level, and is mostly at the tactical level.

The Government announced on 29 May 2018, the International Day of UN Peacekeepers, financial contributions for peacekeeping training to two institutions: École de Maintien de la Paix Alioune Blondin Beye de Bamako or EMP Bamako, and Peace Operations Training Institute or POTI, which is US-based. Each institution was offered $1 million. This does not demonstrate international leadership in training, but it does assist these two particular institutions financially.

As part of the Elsie Initiative for women in peace operations, Canada has helped train police women in Zambia, and military women in Ghana. This programme was announced in November 2017 but did not start the actual training programmes unitl the new century. Canada also provided training for "engagement teams" (first female and then mixed).

The United Nations was counting on Canada to provide trainers for its courses at the Regional Services Centre Entebbe or RSCE in October 2018 but Canada did not send the promised trainers. Also, Canadian assistance to the Women's Outreach Course of the UN Signals Academy or UNSA, located at RSCE, has not yet materialized, even though the Elsie Initiative would seem to be an logical source of funds, given the Initiative's goal of increasing women's participation in peacekeeping.

Canada has provided $500,000 to the UN for a Joint Operations Centre or JOC simulation ("mock JOC") to enhance training in Entebe. Canada also helped establish UN Engagement Platoon training courses in Entebbe (pdf).

The Canadian Armed Forces (specifically the Canadian Defence Academy) declined to provide the United Nations with digital simulations (www.peacekeepingsim.net) for UN training of peacekeepers, though these had been developed by academics willing to offer the fruits of this work for free. So other countries took the lead in the void left by Canada. The simulation has been tested and used in a half-dozen countries. It is now available for free online at https://www.peacekeepingsim.net/pks1-investigating-atrocity-web-build/.

Conclusion: very little of the promised leadership in peacekeeping training has been shown. Significant opportunities were missed.

INTELLECTUAL/POLITICAL/POLICY CONTRIBUTIONS^

In the past, Canada provided great contributions to the evolution of UN policies and practice, with the creation of the first peacekeeping mission called UNMOGIP in 1948, and especially the first peacekeeping forces called UNEF in 1956 and UNFICYP in 1964. Later it led in the development of the concepts of Responsibility to Protect or R2P in 2001, the Protection of Civilians or POC in 1999, and human security more generally. It also helped pioneer the use of panels of experts for sanctions monitoring, e.g., Angola 1999, which often happen in conjunction with peace operations.

During the tenure of the Harper government, no intellectual initiatives were undertaken, even as the United Nations made tremendous progress in developing POC, peacekeeping-intelligence, as well as better training and equipping of peacekeepers. The Trudeau government made a major contribution in one area: child soldiers. Thanks mostly to the work of the Romeo Dallaire Child Soldiers Initiative, the Vancouver Principles on "Peacekeeping and Preventing the Recruitment and Use of Child Soldiers" were adopted at the 2017 Vancouver ministerial and have been endorsed by over 80 countries. The contribution to Women, Peace and Security has been more by example, i.e., percentage women deployed in 2019, and financial contributions than by intellectual contribution. In the area of peacekeeping technology innovation, Canada did provide the UN with one gratis personnel for one year, namely Walter Dorn (author of this webpage) in 2017-18. He served as the UN's Innovation and Protection Technology Expert.

For decades, Canada has consistently chaired the Working Group of the Special Committee on Peacekeeping (aka Committee of 34 or C34, from the original number of members of the committee). The Working Group develops the draft of the annual C34 report, which is an important document in the United Nations since it expresses (by consensus) the views of the nations contributing to UN peacekeeping. Some years, the negotiations can be quite difficult because of the range of positions on major issues. In 2020, Canadian diplomats had to work hard to secure consensus, particularly after some nations refused to accept the wording from previous years as acceptable.

The Minister of National Defence created the Dallaire Centre for peace and Security in June 2019 but the results of this centre are not visible to the public. One area of focus is on the Vancouver Principles.

Conclusion: With the exception of the Vancouver Principles on child soldiers and peacekeeping, led by the non-governmental Dallaire initiative (now Dallaire Institute), little or no intellectual leadership in peacekeeping has been shown by the current government.

CONCLUSIONS^

Trudeau Government

In three election campaigns, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau promised Canadians to "re-engage" in UN peacekeeping. After the 2019 election, tasked his Defence and Foreign Ministers to "expand Canada’s support for United Nations peace operations" (Defence Minister Mandate letter, 2019). For the 2021 election, the Liberal Party Platform (pdf) pledged to "renew Canada's commitment to peacekeeping efforts." The Trudeau governments has not lived up to these promises to re-engage in UN peacekeeping. Overwhelming evidence shows that it has gone backwards. In December 2024, at the end of Trudeau's time in office, the contribution reached the lowest level of personnel contribution (26) since the creation of the first peacekeeping force in 1956. And the number female Canadian military personnel in UN peace operations had fallen to merely one (1).

For a single year in 2018/19, the air force contribution to the UN's Mali mission was substantial and valued by the world organization but it lasted only the one year. In addition, a new means of cross-mission air-transport assistance was established by Canada in 2019, which is also commendable, but it is only one C-130 tactical aircraft for fifteen days of UN service every three months. And while the Air Force experienced an increased contribution under the Trudeau government, the Canadian Army did not. It has not rotated troops in UN peacekeeping since the last century. Also, in the 1990s, the Canadian Army provided nine military leaders of UN missions, but none since. Canada is far behind its contribution levels of the past and behind scores of other nations, in terms of numbers, leadership and hardship.

Canada did not re-engage in UN peace operations as promised in several elections since 2015. In its nearly decade in power, the Trudeau government provided 50% FEWER peacekeepers than the Harper government, calculated by comparing the average monthly contribution over their respective decades in office. The deployment of a long-promised QRF has not materialize.

The NATO mission in Latvia has clearly been prioritized over UN missions. This has been a sustained contribution over many years, with far greater numbers of personnel deployed (200+), and with much larger funding.

Ironically, the same month that Canada hosted a peacekeeping pledging conference in Vancouver in November 2017, the number of Canadian uniformed personnel in UN peacekeeping was lower than at any other point since the creation of the first peacekeeping force in 1956. It decreased even further in the months afterwards to 40 in May 2018 and then to 34 by end of September 2020. Even with the increase in Mali from July 2018 to August 2019, the average monthly contribution of the Trudeau government since it assumed power in 2015 is still only about half of the previous government: on average, 78 uniformed personnel for the Trudeau government in the period 2015-24 and 157 for the Harper government, 2006-15.

Defence Ministers Sajjan, Anand and Blair have not shown leadership on peacekeeping. In fact, Sajjan made Canada's fulfilment of its 2017 Vancouver commitments very conditional on the UN action. Rather than fulfilling the promises and offering much needed support to the world organization, in the House of Commons Defence Committee he added a burden: "Once we have the confidence through the UN that we'll have four to five nations as a part of it, then we as a government can consider getting into a rotation. ... we need to make sure that the mission is right, the troops that we have provided are going to have the right impact, and they will make the decisions accordingly ..." (see Sajjan, 2020). This is another case of "paralysis by analysis," where significant opportunities and UN experience were lost as Canada continued to dither and delay in keeping its promises.

The Mali deployment did not signal a "re-engagement" in UN peace operations since the deployment of the aviation task force was relatively short-term: one year plus one month for the aeromedical component. It was not renewed. As noted, Canada announced on 19 March 2018 that it would provide the UN mission in Mali with an aviation task force of 6 helicopters and an aeromedical team. The deployment came to 8 helicopters after negotiations with UN headquarters. This substantial contribution became fully operational in August 2018 but the commitment was of short duration, less than the countries that preceded Canada. Furthermore, it was not a complete replacement for the German capability that was withdrawn in June 2018 after one-and-a-half years of service. And even with the Mali contribution, Canada's peak contribution during Trudeau's terms has been just one-third, roughly, of Canada's pledged military contribution of up to 600 personnel.

Furthermore, other pledges are not being implemented. The promised Quick Reaction Force has not been deploying since it was pledged by Trudeau at the Vancouver ministerial in 2017. There is no deployment date or place in sight. Similarly, a new mission for Canadian police contributions has not yet been announced. During Trudeau's term, Canada reached the lowest police contribution since 1992, just 7 personnel in July 2020. Similarly, the number of deployed women in peacekeeping fall precipitously. At the end of Trudeau's term, only one (1) military women was deployed in UN peacekeeping operations. For the promised deployment of C-130 Hercules aircraft to Entebbe, a creative proposal to serve multiple UN missions, the UN-Canada MOU took almost two years to negotiate. Though August 2018 was the expected deployment month for the service, the agreement was not reached until a year later. And that service was suspended just as the UN faced the challenges of Ebola and COVID-19. The agreement was extended for another year in August 2020, to the credit of the Canadian government, and again in 2024.

With the Air Force making the majority of the UN contribution, the Army has been left in limbo in peacekeeping, having deployed no units to UN operations during Trudeau's term.

Carney Government

Mark Carney was sworn in as Prime Minister in March 2025. His Liberal Party's election platform stated: "It was a Canadian who came up with the concept of a UN peacekeeping force" and stated "if needed, [Canada will] build on our peacekeeping heritage and step up to guarantee Ukraine’s security."

Foreign Minister Anita Anand made pledges at the 2025 Peacekeeping Ministerial (Berlin) to continue Canada's contribution of a transport aircraft (C-130, "subject to aircraft availability", previously 15 days every three months), and to provide funding to help a number of Canadian and other projects in training, research and advocacy. Just as when she was a new Minister of National Defence in 2021 and participated in the Seoul ministerial (December 2021), she did not use the Berin Peacekeeping Ministerial to make any new pledges in personnel or units or indicate that Canada would fulfill its promise to provide a Quick Reaction Force. Instead, Canada pledged only funding in Seoul (Anand, UN webTV, minutes 1:33:45- 1:39:40) and continued this tradition of dollar diplomacy in Berlin.

In the UN General Assembly, Anand stated (September 29, 2025):

From promoting UN peacekeeping operations during the Suez Crisis to spearheading the Ottawa Treaty banning anti-personnel mines, Canada has consistently been an innovative leader on global issues. That spirit continues to guide us today. Canada does not shrink from global challenge. Canada does not retreat from duty. Canada does not walk away from building and strengthening peace.

Time will tell how this new government is able to contribute to the peacekeeping instrument as a means to strengthen peace.

One fact can already be stated. Under the Carney government, the number of women military deployed in peacekeeping reach rock bottom: 0.

Under the Trudeau government, Canada consistently failed to meet the UN targets, though it continued to champion the Elsie Initiative to promote women's participation in peacekeeping. This lack of alignment between advocacy and practice does not bode well for the future. But will the Carney government do better?

Overall

The governments of this century have brought about a major decline in Canadian contributions to UN peacekeeping. Compared to the 1,000 peacekeepers provided for 40 years (1956-1996), and the high of 3,300 peacekeepers (July 1993), the contributions have been only a tiny fraction (roughly 1% of that high). The governments, both Liberal and Conservative, have not heeded the call of Lester B. Pearson, made in his 1957 Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech:

We made at least a beginning then. If, on that foundation, we do not build something more permanent and stronger, we will once again have ignored realities, rejected opportunities, and betrayed our trust. Will we never learn?

This webpage is updated on a quarterly basis after UN statistics are released. Periodic op-eds on this subject were published (e.g., Toronto Star on 22 August 2019, the Globe & Mail on 15 September 2023 and 8 October 2024.).

REFERENCES^

Anand, Anita, Address to the Peacekeeping Ministerial in Seoul, South Korea, 7 December 2021, UN webTV, minutes 1:33:45- 1:39:40.

Canada, Department of National Defence, "Pledges," 2017 UN Peacekeeping Defence Ministerial, Vancouver, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/campaigns/peacekeeping-defence-ministerial/pledges.html.

Canada, Department of National Defence, Directorate of History and Heritage, Operations Database: DOMREP; ONUC: ONUCA: UNDOF; UNEF; UNEFII; UNFICYP; UNGOMAP; UNIFIL;

UNIPOM; UNMOGIP; UNTAG; UNYOM.

Canada, Department of National Defence,"Minister Sajjan Reaffirms Peace Operations Pledge at UN Defence Ministerial," https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/news/2016/09/minister-sajjan-reaffirms-peace-operations-pledge-defence-ministerial.html. Quote: "Canada stands ready to deploy up to 600 Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) personnel for future UN peace operations," 8 September 2016.

Canada, DND, "Supplementary estimates (A) line items - National Defence," 2020, https://www.canada.ca/en/department-national-defence/corporate/reports-publications/proactive-disclosure/supp-estimates-a-2020-21/supp-estimates-a-line-items.html#toc1. Also has sections for peacekeeping (Smart Pledges, Elsie Initiative, Vancouver Principles)

Canada, Global Affairs Canada (GAC), "Canada announces renewed commitments to peacekeeping at 2021 United Nations Peacekeeping Ministerial," html ,2021.

Canada, House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence, "Canada’s Role in International Peace Operations and Conflict Resolution," 2019 (pdf, 2 MB) (Fr: pdf)

Canada, Prime Minister, "Canada bolsters peacekeeping and civilian protection measures," News Release, 15 November 2017,

https://pm.gc.ca/eng/news/2017/11/15/canada-bolsters-peacekeeping-and-civilian-protection-measures.

Canada, Privy Council, "Mandate Letter Tracker: Delivering results for Canadians," https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/campaigns/mandate-tracker-results-canadians.html, accessed 8 February 2018.

Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, "Canada offering 200 ground troops for future UN peacekeeping operations," http://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/peacekeeping-plan-trudeau-vancouver-1.4403192, 15 November 2017. Trudeau Quote from Ministerial on 15 November 2017: "We are making all these pledges today, because we believe in the United Nations and we believe in peacekeeping," he said. "What we will do is step up and make the contributions we are uniquely able to provide."

Canadiansoldiers.com, “Peacekeeping,” http://www.canadiansoldiers.com/history/peacekeeping.

Davis, Karen, Erinn C. Squires, and Ingrid Lai, “Canadian Military Women and Peace Support Operations: Preliminary Scoping of Deployment Patterns,” paper delivered to the Canadian Peace Research Association, Congress of Humanities and Social Sciences, 4 June 2021.

DND, "UN Request," ATIP file A201901145_2020-09-30_11-37-21, p.12 and 20. (Also discusses priorities of France and Germany.)

Dorn, A. Walter and Joshua Libben, "Preparing for peace: Myths and realities of Canadian peacekeeping training," International Journal, Vol. 73, Iss. 2, pp. 257-281 (26 July 2018) html, pdf. Longer 2016 Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) and the Rideau Institute report: html, pdf.

Durch, William J., The Evolution of UN Peacekeeping: Case Studies and Comparative Analysis, St Martin’s Press, New York, 1993.

Goncharova, Daria. "Canada and ‘Re-engaging’ United Nations Peacekeeping: A Critical Examination." University of Manitoba (MA thesis), Winnipeg, 2018. pdf:

https://mspace.lib.umanitoba.ca/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1993/32887/goncharova_daria.pdf

Sajjan, Harjit, Defence Minister, Address to the UN Security Council, 28 March 2018, video at http://webtv.un.org/watch/part-2-collective-action-to-improve-united-nations-peacekeeping-operations-security-council-8218th-meeting/5760429007001/?term=, 42:00-51:44.

Sajjan, Harjit, Defence Minister, "Testimony before the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence," 11 March 2020, at https://www.ourcommons.ca/DocumentViewer/en/43-1/NDDN/meeting-3/evidence#Int-10805065.

Trudeau, Justin, Prime Minister, Minister of National Defence Mandate Letter, 12 November 2015, html.

Trudeau, Justin, Prime Minister, Minister of National Defence Mandate Letter, 13 December 2019, https://pm.gc.ca/en/mandate-letters/2019/12/13/minister-national-defence-mandate-letter

Trudeau, Justin, Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs, update of 1 February 2017, html.

Trudeau, Justin, Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs, 13 December 2019, https://pm.gc.ca/eng/minister-foreign-affairs-mandate-letter

United Kingdom, "UN Peacekeeping Defence Ministerial: London 2016," https://www.gov.uk/government/topical-events/un-peacekeeping-defence-ministerial-london-2016. Final Report (pdf).

United Kingdom, "UN Peacekeeping Ministerial – pledge slides PPT", https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/556825/Pledge_slide_show_-_final_for_media_2.pdf.

United Nations, "Troop and Police Contributors," https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/troop-and-police-contributors.

United Nations, Department of Peacekeeping Operations / Department of Field Support, "Current and Emerging Uniformed Capability Requirements for United Nations Peacekeeping," issued periodically, including December 2016 pdf, May 2017 pdf and August 2017 pdf.

United Nations, Department of Public Information, The Blue Helmets: A Review of United Nations Peace-Keeping, 2nd ed.., New York, N.Y., United Nations, 1992.

World Federalist Movement – Canada (WFMC), “Canadians for Peacekeeping”, https://peacekeepingcanada.com/, which provides a copy of this webpage at https://peacekeepingcanada.com/tracking-the-promises-canadas-contributions-to-un-peacekeeping/.

BACKGROUND ANNEXES^

A.1: Canada's pledges, as recorded in peacekeeping ministerials (London, Vancouver, New York and Seoul) and the government's Mandate Letter Tracker

London (2016) and Vancouver new pledges (2017):

New York (2019):

2019 (Mandate Letter Tracker, status when discontinued in June 2019):

![]()

Seoul (2021):

Accra (2023):

A.2: Canadian contributions of uniformed personnel from 1950 to 2021

(maximum of each year)

Sources: Canada DND, Canadiansoldier.com, Durch, Goncharova, UN DPI

Mission Acronyms: Largest Cdn Contributions (at the time)

MINUJUSTH: United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (2017-19)

MINUSTAH: United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (2004-17)

UNDOF: United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (1974-)

UNEF: United Nations Emergency Force (1956-67)

UNEF II: United Nations Emergency Force (1973-79)

UNFICYP: United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (1964-)

UNMEE: United Nations Mission in Ethiopia and Eritrea (2000-08)

UNMISS: United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan (2011-)

UNPROFOR: United Nations Protection Force (1992-95)

UNOSOM: United Nations Operation in Somalia (1992-95)

UNTAC: United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia (1992-93)

UNTSO: United Nations Truce Supervision Organization (1948-)

Figure A.3: Canada's rank among nations contributing uniformed personnel to UN peacekeeping, 1991 to 2023

(Lowest rank since Pearson's proposal for a peacekeeping force (1956) was 81st, reached in May 2018, two months before the Mali deployment)

Figure A.4. Contribution by six-month average, from 2000 to 2018 (December), showing governments in power at the time (graphics by Munich Security Report 2019 using data from Dorn)

Figure A.5. Women in Canadian Armed Forces deployed to UN peace operations over the decade 2011-2021 by Fiscal Year

(Source: Davis et al, 2021; using data from Department of National Defence)

(deployment means on the operation for more than 30 days, starting in the fiscal year specified)

Figure A.6. Percentage of women in each occupational group of the CAF and percentage women deployed in each occupational group

(Source: Davis et al, 2021; using data from Department of National Defence)

Figure A.7. Women's representation in Canada's military contribution (30 Nov 2021) falls below UN target for 2021 (18%)

UN target for 2022: 19%.

SELECTED QUOTES FROM MINISTERS

"The time for change is now and we must be bold" (Minister Sajjan speech to UN Security Council, 28 March 2018, copy).

GOVERNMENT'S SELF-EVALUATION (2018–20)^

Until 2020, the government provided its own self-evaluation of the results of the promises from the PM's mandate letters at canada.ca/results, which redirects to https://www.canada.ca/en/privy-council/campaigns/mandate-tracker-results-canadians.html. In October 2018, it listed the peacekeeping commitments as "Underway – on track," defined as "progress toward completing this commitment is unfolding as expected." In December 2018, this was downgraded to "Actions taken, progress made." That self-appraisal status stayed the same until the site was discontinued. The government's self-evaluation that fulfilment of its peacekeeping promises was "on track" in June 2019 was inaccurate. The government's downgraded self-evaluation of "actions taken, progress made," starting January 2019 and continuing to October 2019, was more accurate but also indicates how far the reality is from the promises. Only one mission has been added by the Trudeau government since 2015: the Mali mission but this support function was provided for only a year. Afterwards the uniformed personnel contribution fall to an all-time low.

Figures A.3. Number of Uniformed peacekeepers deployed by the UN (1990–2024)

Table A.1 Canadian personnel contributions (M, F) to UN peace operations by month

Abbreviations

M, F: Male, Female

MSO: Military Staff Officer

Troops: military personnel deployed in units

UNMEM: UN Military Expert on Mission (mostly UN Military Observers)

UNPOL: UN Police

31 August 2019

| Mission | Troops | Mil Experts |

Staff |

Mil Total |

Police | Mission Total |

| MINUSMA | 69 (58, 11) | 8 (5, 3) | 77 (63, 14) | 9 (6,3) | 86 (69, 17) | |

| MINUJUSTH | 18 (6, 12) | 18 (6, 12) | ||||

| UNMISS | 4 (4, 0) | 7 (4, 3) | 11 (8,3) | 11 (8, 3) | ||

| MONUSCO | 8 (7, 1) | 8 (7, 1) | 8 (7, 1) | |||

| UNTSO | 4 (4,0) | 4 (4,0) | 4 (4, 0) | |||

| UNFICYP | 1 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 1) | |||

| Totals | 69 (58, 11) | 9 (8, 1) | 23 (16, 7) | 101 (82, 19) | 27 (12, 15) | 128 (94, 34) |

30 September 2019 (pdf)

| Mission | Troops | Mil Experts |

Staff |

Mil Total |

Police | Mission Total |

| MINUSMA | 0 | 5 (3, 2) | 5 (3, 2) | 12 (8, 4) | 17 (11, 6) | |

| MINUJUSTH | 8 (3, 5) | 8 (3, 5) | ||||

| UNMISS | 4 (4, 0) | 7 (4, 3) | 11 (8,3) | 11 (8, 3) | ||

| MONUSCO | 8 (7, 1) | 8 (7, 1) | 8 (7, 1) | |||

| UNTSO | 4 (4,0) | 4 (4,0) | 4 (4, 0) | |||

| UNFICYP | 1 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 1) | 1 (0, 1) | |||

| Totals | 0 | 8 (8, 0) | 21 (14,7) | 29 (22, 7) | 20 (11, 9) | 49 (33, 16) |

31 October 2019

| Mission | Totals | ||||

| UNMEM | Troops | UNPOL | MSO | Mission | |

| BINUH | 0 | 0 | 4 (0,4) | 0 | 4 (0,4) |

| MINUSMA | 0 | 0 | 12 (8,4) | 5 (3,2) | 17 (11,6) |

| MONUSCO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (6,1) | 7 (6,1) |

| UNFICYP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0,1) | 1 (0,1) |

| UNMISS | 4 (4,0) | 0 | 0 | 8 (4,4) | 12 (8,4) |

| UNTSO | 4 (4,0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4,0) |

| Totals | 8 (8,0) | 0 | 16 (8,8) | 21 (13,8) | 45 (29,16) |

31 December 2019

| Mission | Totals | ||||

| UNMEM | Troops | UNPOL | MSO | Mission | |

| BINUH | 0 | 0 | 3 (0,3) | 0 | 3 (0,3) |

| MINUSMA | 0 | 0 | 16(9,7) | 5 (3,2) | 21 (12,9) |

| MONUSCO | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (8,0) | 8 (8,0) |

| UNFICYP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0,1) | 1 (0,1) |

| UNMISS | 4 (4,0) | 0 | 0 | 7 (4,3) | 11 (8,3) |

| UNTSO | 4 (4,0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (4,0) |

| Totals | 8 (8,0) | 0 | 19 (9,10) | 21 (16,6) | 48 (32,16) |

31 January 2020

| Mission | Location | Contribution type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Experts | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Staff | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Experts | 3 | 0 | 3 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Staff | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Staff | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| 33 | 12 | 45 |

29 February 2020

| Mission | Location | Type | M | F | Tot |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil staff | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Mil experts | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Mil | 20 | 9 | 29 | ||

| Police | 17 | 0 | 17 | ||

| 35 | 11 | 46 |

31 March 2020

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 8 | 6 | 14 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil staff | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Mil experts | 3 | 4 | 7 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Mil | 23 | 6 | 29 | ||

| Police | 8 | 6 | 14 | ||

| Totals | 31 | 12 | 43 |

30 April 2020

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil experts | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Mil staff | 3 | 3 | 6 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Mil | 21 | 4 | 25 | ||

| Police | 6 | 4 | 10 | ||

| Totals | 27 | 8 | 35 |

31 May 2020

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil experts | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Mil | 20 | 4 | 24 | ||

| Police | 6 | 4 | 10 | ||

| Totals | 26 | 8 | 34 |

30 June 2020

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil experts | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Mil | 20 | 4 | 24 | ||

| Police | 6 | 4 | 10 | ||

| Totals | 26 | 8 | 34 |

31 August 2020

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 3 | 4 | 7 |

| Mil staff | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil experts | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 3 | 7 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 6 | 0 | 6 |

| Mil | 21 | 6 | 27 | ||

| Police | 3 | 4 | 7 | ||

| Totals | 24 | 10 | 34 |

31 October 2020

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Mil staff | 2 | 2 | 4 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Police | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil experts | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mil staff | 6 | 4 | 10 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Mil | 20 | 7 | 27 | ||

| Police | 7 | 4 | 11 | ||

| Totals | 27 | 11 |

38 |

31 March 2021:

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 9 | 2 | 11 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Police | 8 | 4 | 12 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil experts | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 2 | 6 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Mil | 23 | 5 | 28 | ||

| Police | 20 | 7 | 27 | ||

| Totals | 43 | 12 |

55 |

30 April 2021

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 10 | 3 | 13 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil staff | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Police | 8 | 5 | 13 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil staff | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil experts | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Mil staff | 4 | 2 | 6 | ||

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil experts | 4 | 0 | 4 |

| Mil | 23 | 5 | 28 | ||

| Police | 21 | 9 | 30 | ||

| Totals | 44 | 14 |

58

|

31 August 2021

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| Mil | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 8 | 1 | 9 |

| Police | 10 | 5 | 15 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Mil | 21 | 5 | 26 | ||

| Police | 20 | 12 | 32 | ||

| Totals | 41 | 17 |

58

|

30 September 2021

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| Mil | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Police | 10 | 5 | 15 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Mil | 20 | 5 | 25 | ||

| Police | 20 | 12 | 32 | ||

| Totals | 40 | 17 | 57 |

31 October 2021

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 7 | 6 | 13 |

| Mil | 3 | 2 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 7 | 1 | 8 |

| Police | 10 | 4 | 14 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 6 | 2 | 8 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Mil | 22 | 5 | 27 | ||

| Police | 19 | 12 | 31 | ||

| Totals | 41 | 17 | 58

|

30 November 2021

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total | |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 8 | 6 | 14 | |

| Mil | 3 | 2 | 5 | |||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 7 | 1 | 8 | |

| Police | 10 | 5 | 15 | |||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 7 | 2 | 9 | |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 5 | 0 | 5 | W% |

| Mil | 23 | 5 | 28 | 18% | ||

| Police | 18 | 13 | 31 | 42% | ||

| Totals | 41 | 18 | 59 | 31% |

30 April 2022

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total | |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 9 | 8 | 17 | |

| Mil | 3 | 2 | 5 | |||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 7 | 1 | 8 | |

| Police | 5 | 6 | 11 | |||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 7 | 1 | 8 | |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 4 | 1 | 5 | W% |

| Mil | 22 | 5 | 27 | 19% | ||

| Police | 15 | 16 | 31 | 52% | ||

| Totals | 37 | 21 | 58 | 36% | ||

| check (TotM+TotF): | 58 |

30 September 2022

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total | Gender Distribution |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 8 | 5 | 13 | |

| Mil | 4 | 1 | 5 | |||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 8 | 0 | 8 | |

| Police | 8 | 7 | 15 | |||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 7 | 2 | 9 | |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 2 | 1 | 5 | |

| Mil | 21 | 5 | 26 | 31% | ||

| Police | 17 | 12 | 29 | 41% | ||

| Totals | 38 | 17 | 55 | 31% |

31 October 2022

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| Mil | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Police | 11 | 9 | 20 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 7 | 2 | 9 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Mil | 21 | 6 | 27 | ||

| Police | 19 | 13 | 32 | ||

| Totals | 40 | 19 | 59 |

Source: UN

28 February 2023:

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Mil | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Police | 12 | 12 | 24 |

| Mil | 8 | 0 | 8 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Mil | 22 | 5 | 27 | ||

| Police | 16 | 15 | 31 | ||

| Totals | 38 | 20 | 58 |

31 March 2023:

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Mil | 4 | 0 | 4 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Police | 13 | 12 | 24 |

| Mil | 7 | 0 | 8 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Mil | 22 | 5 | 27 | ||

| Police | 17 | 14 | 31 | ||

| Totals | 39 | 19 | 58

|

30 April 2023:

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Mil | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Police | 11 | 11 | 22 |

| Mil | 7 | 0 | 7 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Mil | 22 | 6 | 28 | ||

| Police | 17 | 13 | 30 | ||

| Totals | 39 | 19 | 58

|

31 May 2023:

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total |

| BINUH | Haiti | Police | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| MINUSMA | Mali | Police | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Mil | 4 | 1 | 5 | ||

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Police | 11 | 11 | 22 |

| Mil | 7 | 0 | 7 | ||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 2 | 2 | 4 |

| Mil | 22 | 6 | 28 | ||

| Police | 17 | 13 | 30 | ||

| Totals | 39 | 19 | 58 |

31 December 2024 (last UN stats from Trudeau's term as Prime Minister)

| Mission | Location | Type | Male | Female | Total | |

| MONUSCO | D.R. Congo | Mil | 8 | 0 | 8 | |

| Police | 2 | 2 | 4 | |||

| UNFICYP | Cyprus | Mil | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| UNMIK | Kosovo | Police | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| UNMISS | S. Sudan | Mil | 7 | 1 | 8 | |

| UNTSO | Middle East | Mil | 4 | 0 | 4 | W% |

| Mil | 20 | 1 | 21 | 5% | ||

| Police | 3 | 2 | 5 | 40% | ||

| Totals | 23 | 3 | 26 | 12% |